The Sad History of the Parthenon Marbles

One of the greatest artistic achievements ever is the Parthenon. Many

sculptures were removed from the temple and transported to England. The

famous "Elgin Marbles" are in London now. But there is a big question:

where should these marbles be? Here, we tell the story of the Parthenon

Marbles, based on the pamphlet "The Parthenon and the Elgin Marbles" by

Epaminondas Vranopoulos , published by the Society for Euboian Studies

in 1985. We would like to thank Mr Vranopoulos for granting us

permission to reproduce extracts from his pamphlet.

One of the greatest artistic achievements ever is the Parthenon. Many

sculptures were removed from the temple and transported to England. The

famous "Elgin Marbles" are in London now. But there is a big question:

where should these marbles be? Here, we tell the story of the Parthenon

Marbles, based on the pamphlet "The Parthenon and the Elgin Marbles" by

Epaminondas Vranopoulos , published by the Society for Euboian Studies

in 1985. We would like to thank Mr Vranopoulos for granting us

permission to reproduce extracts from his pamphlet.

You can download the complete pamphlet "The Parthenon and the Elgin

Marbles" by Epaminondas Vranopoulos. This is still a copyright work but

you will not be charged for downloading the pamphlet.

Plain text .zip file (size 25 kb):

pamphlet1.zip

containing the file vran.txt.

HTML .zip file (size 25kb):

pamphlet2.zip

containing the file vran1.htm.

Part One: The Construction of Parthenon

"The Greeks were gods!" - Henry Fuseli, Swiss painter, on seeing the Marbles.

After their victory against the Persians at Plataea in 479BC the Athenians returned to their abandoned city and found all the buildings on the Acropolis had been laid waste.

Pericles wanted to rebuild the city and make it an artistic and cultural

as well as political hellenic centre. During the thirty years of

Pericles' rule, many buildings were erected like the Parthenon, the

Propylaea and many others.

Pericles wanted to rebuild the city and make it an artistic and cultural

as well as political hellenic centre. During the thirty years of

Pericles' rule, many buildings were erected like the Parthenon, the

Propylaea and many others.

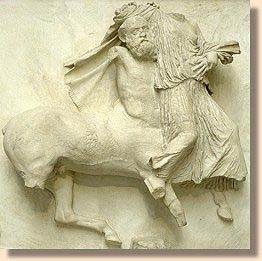

The general artistic supervision of the Acropolis buildings was assigned

to Pheidias who distinguished himself by producing decorations that were

unique in magnificence.

In 439BC the Parthenon was dedicated to the goddess Athena and it took

15 years to complete. This is a remarkably short time when one considers

the principles of architecture employed, some of which are still unknown

to us.

In 450AD the Parthenon was turned into a Christian church dedicated to

the Virgin Mary, but in 1204, when the Franks occupied Athens they

turned the Parthenon into a Catholic church and when the Turks arrived

in 1458 the Parthenon became a mosque with Turkish houses built around

it.

In 1674, the French ambassador, the Marquis de Nointel, paid a visit to

Athens accompanied by Jacques Carrey who made drawings of the Parthenon.

Carrey's drawings show that at that time the Parthenon still remained

intact.

Thirteen years later, in 1687, the Venetian general Francesco Morosini

laid siege to the Acropolis. He bombarded the Acropolis, even though he

knew that the Turks were storing gunpowder there. The result was an

explosion which destroyed much of the Parthenon.

Part two: The Stripping of the Parthenon

"Lord Elgin may now boast of having ruined Athens." - Anonymous Greek, 1810.

Thomas Bruce, seventh earl of Elgin, was the British ambassador at

Constantinople in 1799 and he wanted to be of service to the Arts by

making his countrymen more familiar with Greek antiquities. He put

together a team of painters, architects and moulders.

The following year, the local Turkish commandant allowed the artists to

make drawings but refused to allow them to take casts or build

scaffolding for a closer look at the sculptures.

In 1801 Elgin obtained a firman , or authority, from the Sultan which

gave him permission to take away any sculptures or inscriptions which

did not interfere with the works or walls of the citadel.

In 1801 Elgin obtained a firman , or authority, from the Sultan which

gave him permission to take away any sculptures or inscriptions which

did not interfere with the works or walls of the citadel.

The looting of the Parthenon began immediately. The sculptures were

lowered from the temple and transported by British sailors on a gun

carriage. On December 26 1801, fearing the French might try to obstruct

his work, Elgin ordered the immediate shipment of the sculptures on the

ship "Mentor" which he had brought for this purpose.

During 1806, one of the Caryatids was removed, as well as a corner of

the Erechtheum, part of the frieze of the Parthenon, many inscriptions

and hundreds of vases.

Others joined in the looting and this incredible activity, which was not

confined to the Acropolis but was carried out throughout Athens and

large parts of Greece, continued for many years. In 1810 Elgin loaded

the last of his booty on the warship "Hydra".

In 1817 two more warships, the "Tagus" and the "Satellite", were loaded

with gravestones, copperware and hundreds of vases. Four years later,

the Greek War of Independence finally brought Elgin's looting to an end.

Part Three: The Elgin Marbles in London

"Quod non fecerunt Gothi, hoc fecerunt Scoti" "What the Goths did not do, the Scots did here" - Graffiti, Athens 1813

It was January 1804 when the first 65 cases arrived in London, where they remained for two years because Elgin had been imprisoned in France.

The maltreatment which the Marbles suffered was unavoidable. They were

placed in the dirty and damp shed and grounds of Elgin's Park Lane house

and remained there for years, decaying in London's damp climate, while

he tried to find a buyer.

The maltreatment which the Marbles suffered was unavoidable. They were

placed in the dirty and damp shed and grounds of Elgin's Park Lane house

and remained there for years, decaying in London's damp climate, while

he tried to find a buyer.

Elgin made attempts to sell the Marbles to the British government but

the price he asked was so high that they refused to buy them. As the

years passed, so the Marbles influenced the lives of people in Britain.

Churches, buildings and houses were built in Greek classical style.

In a letter written by Elgin in 1815, he admitted that the Marbles were

still in the coal shed at Burlington House, decaying from the

destructive dampness.

Finally, in 1816, the Marbles were sold to the British government and

were at once transferred from Burlington House to the British Museum,

where a special gallery was eventually built for them by Sir Joseph

Duveen at his own expense.

In December 1940 a Labour MP, Mrs Keir, asked the Prime Minister,

Winston Churchill whether the Marbles would be returned to Greece in

partial recognition of that country's valiant resistance to the Germans

and the sacrifices of its people. The answer was negative. At the time

that Mrs Keir tabled her question, there was a large number of letters

published in the Times favouring the return of the Marbles to Greece.

In 1941 the head of the Labour Party, Clement Attlee, who was a member

of the wartime coalition government, replied to Mrs Keir's question,

saying that there was no intention to take any legal steps for the

return of the Marbles.

Part Four: Contemporary comments on Lord Elgin's looting

"He (Elgin) looted what Turks and other barbarians considered sacred." - J. Newport MP

Edward Clarke, in his book "Travel to European Countries", published in 1811, wrote one of the most famous descriptions of the actual operations on the Acropolis by Lord Elgin's workteam under the supervision of Lusieri. According to Clarke, who witnessed the removal of the metopes, it was a fantastic and marvellous sculpture. But tragedy struck when a part of the Pentelic marble collapsed under the pressure of Elgin's machines and Clarke states that even the Turkish commander cried as the marble was smashed to pieces.

Clarke also makes the point that Elgin's workteam didn't ruin the

Parthenon by mistake, but they also cut the marble into smaller pieces

for easier transport.

Clarke also makes the point that Elgin's workteam didn't ruin the

Parthenon by mistake, but they also cut the marble into smaller pieces

for easier transport.

He was also aware that Pheidias and his fellow-sculptors had designed

the decorations to the Parthenon in such a way that they could be seen

at their best from below, not at eye level in a museum.

He concludes by saying that the shape of the temple suffered damage

greater than that suffered by Morosini's artillery, that a great

iniquity had been committed and that the English government could have

demanded that the Turkish government took measures to protect the

sculptures.

Edward Dodwell states in refutation of the British argument that the

Greeks weren't indifferent to the preservation of the monuments. Many

had complained about the ruination to the Sultan because he had given

permission to Elgin to make his plans. He also says that he felt

humiliation at being present at the looting of the most exquisite

sculptures and architectural members. He adds that the arts in England

could have benefited from castings of Pheidias' sculpures and ends by

saying that not only was sacrilege committed but also the work had been

assigned to people who only cared for their individual interests.

Thomas Hughes, an English clergyman, gives a shocking picture of the

plunder of the Acropolis: "Tympana capitals, entablature and crown, all

were lying in huge heaps that could give material for the erection of an

entire marble palace."

Thomas Hughes, an English clergyman, gives a shocking picture of the

plunder of the Acropolis: "Tympana capitals, entablature and crown, all

were lying in huge heaps that could give material for the erection of an

entire marble palace."

The English painter Hugh Williams admitted that the Elgin Marbles would

certainly have contributed to the progress of the arts in England but he

didn't accept the right to uproot them from Greece.

Lord Broughton also mentions the damage to the Parthenon and accuses

Elgin of having planned to remove the entire temple of Theseum

(Hephaestus).

Francis Douglas, a British MP, assured Parliament that the Greeks

admired the remnants of the Parthenon and that even the Turks had begun

to appreciate their value. He also said that every sculpture of the

Parthenon reminds us of the chisel of its creator and those for whom it

was created. He ended by expressing his great disappointment at the

impudence of the hands that were not afraid to dislocate the magnificent

objects of the Parthenon and he praised Chateaubriand, who had charged

Elgin with sacrilege.

Part Five: British views on the return of the Marbles

"The marble caused us a lot of difficulties and I had slightly to become a barbarian." - Lusieri to Elgin

Elgin's second attempt to sell the Marbles to the British government led

to a debate in Parliament where Sir John Newport MP said about Lord

Elgin: "The Honourable Lord has taken advantage of the most

unjustifiable means (i.e. bribery) and has committed the most flagrant

pillages. "

On the same day, the speaker of Parliament noted in the calendar: "Lord

Elgin's petition has been filed. His ownership rights on the collection

have been contested; his conduct has also been censured."

Among the first people to criticise Lord Elgin was H. Hammersley MP. He

advocated that if any future Greek government demanded the Marbles back,

England should return them without any further procedure or negotiation.

Dodwell and Clarke suggested at least the return of the Erectheum

cornice and the Ionic column.

Also in 1890 an editorial by Franklin Harrison, which appeared in the

magazine "19th Century", entitled "Return the Elgin Marbles!" maintained

that the sculptures were more dear to the Greeks than to the British.

Besides that, Philip Sassoon MP, and Private Secretary to the Prime

Minister at the time, wrote in the Times in 1928 that the splendid ruins

of the Parthenon and the bright air of Athens would be a more suitable

place for the most harmonious sculptures in the world, than the British

Museum.