A TOUR OF GREEK ART

The sea has always been there, alive throughout the ages, appearing with a thousand faces, as an element of inspiration or as a monster, to challenge the Greeks sometimes with tranquility and sometimes with wrath when they set sail for Aia, Ilium, Paphos, Engomi and the Achaean Coast or, later on, for Famagusta and Kyrenia.

They had no other option. They had to turn to the sea since their land was small and barren. They always looked beyond the horizon, into the unknown, where all their dreams could, in a miraculous way, come true.

They didn't see the ships that would take them on their journeys merely as a means of transport. For them their ships were alive, an extension of their own being, beautiful, with suitable lines. They had sails instead of wings and glided on the water with the grace of migratory birds.

In the conscience of the Greeks reality and legend fused into one entity. Thus, in antiquity we see Dionysus travelling across the seas of history and myth surrounded by peaceful dolphins with a climbing vine on the mast instead of a sail. Similarly, the prophet lezekiel wrote on a drinking-cup, blending dream and reality:

"Let the sea mourn."

In the Byzantine representation of the "Second Coming" the sea is depicted as a woman riding on a sea monster and holding a ship in her palm. The view has a dramatic tone, the waters are stormy and the image of the sea reveals deep mourning.

In the Byzantine representation of the "Second Coming" the sea is depicted as a woman riding on a sea monster and holding a ship in her palm. The view has a dramatic tone, the waters are stormy and the image of the sea reveals deep mourning.

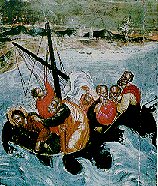

In the icon with Jesus Christ pacifying the sea, the sea is pictured during a storm with the waves realistically painted. An apostle is furling the swollen sail, the others look frightened and Peter is drawing near to awaken Jesus. In the background some ships are moored near the shore. In this work the rich, bright Byzantine colours and stylized figures mingle with a realistic representation of nature.

In the book of the life of St. Minas, we read about how the Saint rescued the servant of a rich Christian from the depths of the sea.

In later years the picture of the ship became an offering, a donation on altars and graves to accompany prayers and souls to heaven.

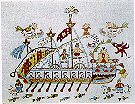

During the dark years of Turkish occupation there was a flourishing of folk art. The masters of those times created a rich tradition embroidering, engraving, carving or hewing mermaids, sailing ships, seamen, marine animals and plants. They lived the dream of the sea, decorating pictures with taste and sensitivity.

During the dark years of Turkish occupation there was a flourishing of folk art. The masters of those times created a rich tradition embroidering, engraving, carving or hewing mermaids, sailing ships, seamen, marine animals and plants. They lived the dream of the sea, decorating pictures with taste and sensitivity.

On the sky above masts and colourful sails there are paradise birds flying, hovering seamen, imaginary animals and other decorative motifs in a proliferation of cheerful colours.

On the sky above masts and colourful sails there are paradise birds flying, hovering seamen, imaginary animals and other decorative motifs in a proliferation of cheerful colours.

Modern Greek seascape painting, which appeared with the establishment of the Greek state, did not draw from the vigorous folk tradition which recounted with craftsmanship and love the Greek people's experi- enc es with the sea. It chose to express itself in a language that was borrowed from the West. It did not go to native shores but sought, instead, inspiration elsewhere.

Constantinos Volonakis rendered the effusive light of the Greek sea with independent touches.

Constantinos Volonakis rendered the effusive light of the Greek sea with independent touches.

loannis Altamouras loved the play of fire on the water and portrayed with rich colours the infinite hues and movement of the waves.

Constantinos Parthenis, one of the most daring investigators of Neohellenic art, sought a personal creative course. In a marvellous har- monization of red and blue he created an ethereal world in which antiquity converges with personal vision.

A.CHRYSOCHOS