The Library of Alexandria -- Ancient and Modern

The Ancient Library

by Prof Moustafa El-Abbadi

The Modern Library

Bibliotheca Alexandrina

Copyright © Hellenic Electronic Center and Professor Moustafa El Abbadi (author) 1998. All rights reserved.

The Universal Library

Alexander the Great -- the Conquests as a source of knowledge

The Founding of the Library and the Mouseion

All the Books in the World

Aristotle's Books

The Hunt for Books

The Egyptian Section of the Alexandria Library

The Papyri: Evidence of Greek and Egyptian Scientific Interchange

"The Writings of All Men"

The Growth of the Library

The Pinakes -- a Bibliographical Survey of the Alexandria Library

The Alexandria Library--"The Memory of Mankind"

Appendix 1 -- The Contents of the Alexandria Library

Appendix 2 -- The End of the Library

References

BIBLIOTHECA ALEXANDRINA--The revival of the Ancient Library of

Alexandria

The institution of libraries and archives was known to many ancient civilisations in Egypt, Mesopotamia, Syria, Asia Minor and Greece; but all and sundry were of a local and regional nature, primarily concerned with the conservation of their own respective national tradition and heritage.

The idea of a universal library, like that of Alexandria, had to wait for historic changes that would help to develop a new mental outlook which could envisage and encompass the whole world.

We owe it primarily to the inquisitive Greek mind, which was impressed by the achievements of its neighbours and which led many Greek intellectuals to explore the resources of Oriental knowledge.

This mental attitude among the Greeks, and the emergence of the concept of

a universal culture, was given full expression in due course when

Alexander embarked on his global expedition.

We are familiar with a Greek literary tradition that preserved a vague memory of eminent Greeks - both legendary and historical - who made the journey to Egypt in the quest of learning (Diod. I. 98. 1-4). In many cases, the accounts are either fictitious or exaggerated, but during the century prior to Alexander's campaign, there is concrete evidence of Greek individuals visiting Egypt in particular, to acquire knowledge; this is reflected in the surviving writings of, for example, Herodotus, Plato (esp. Phaedo and Timaeus), Theophrastus (Athen.2. 42b) and Eudoxus of Cnidus (D. L. 8. 86-90).

It may be relevant, at this point to cite the example of Eudoxus, whose subsequent influence seems to have had bearings on the beginnings of the Library in Alexandria.

Diogenes Laertius, in introducing this outstanding astronomer and mathematician, enumerates among his sources, the Pinakes of Callimachus and also a work of Eratosthenes addressed to Baton, both writers known to be extremely well informed on Greek science and scientists, especially when related to Egypt.

Eudoxus, we are told, came to Egypt (c. 350 BC.) with letters of introduction from Agesilaus to Nectanebo II, who in turn introduced him to the priests with whom he spent 16 months studying astronomy. He was entrusted to the special care of Chonouphis, a priest from Heliopolis, the highly reputed centre of learning in Egypt at that time.

While in Egypt, Eudoxus composed a book on astronomy entitled The Eight Year Cycle (Oktaeteris) and, according to Eratosthenes, the work called Dialogue of Dogs may have been a translation by Eudoxus from the Egyptian. This biographical data, with its implied Egyptian influence, has more than once been subjected to disparaging criticism.1

Photo: Part of a column from a payrus roll containing Aeschines' "Against Ctesiphon"

Alexander's conquests as a source of knowledge

Against this background of avid hunger for knowledge among the Greeks, Alexander launched his global enterprise in 334 BC. which he accomplished with meteoric speed until his untimely death in 323 BC.

His aim throughout, had been not only restricted to conquering lands as far as India, bur also to explore them He therefore dispatched his companions, generals as well as scholars, to report to him in detail on regions previously unmapped and uncharted.

His campaigns therefore resulted in a "considerable addition of empirical knowledge of geography" as Eratosthenes later remarked. (ap.Strabon 1.2.1; 2.1.6.)

The reports he had acquired, survived and motivated an unprecedented movement of scientific research and study of the earth with its natural, physical qualities and inhabitants. The time was pregnant with a new spirit that engendered renaissance of human culture; and it was in this exhilarating atmosphere that the great Library and Mouseion saw the light of day, in Alexandria.

The Founding of the Library and the Mouseion

The founding of the Library and the Mouseion, is unquestionably connected with the name of Demetrius of Phaleron, a member of the Peripatic school and former Athenian politician. But there are two conflicting traditions as regards the person of the king who commissioned this double project.The older one, which originated with Aristeas (Letter, 9-10 IInd cent. BC.) favoured Ptolemy II as founder in association with Demetrius, whereas at variance with this tradition, Iraneaus in the IInd cent. AD. (III 21.2 ) expressly gave the credit to Ptolemy I, son of Lagos.

However the opinion among scholars is almost unanimous now, in favour of Ptolemy I, at whose court c. 297 BC. Demetrius sought refuge after his fall from power in Athens and became his trusted advisor.

Furthermore, we know that Demetrius fell into disfavour with Ptolemy II, and did not long survive his accession to the throne (Diog. L.5.78; Cic. Pro C. Raberio Postumo 23).2

In view of these events, it is obvious that it was Ptolemy I, Soter who, c. 295, commissioned Demetrius with the task of founding the Library and the Mouseion. The choice was most appropriate, for Demetrius, besides being a brilliant politician, was also a most prolific writer "whose learning and versatility" was highly thought of by Diogenes Laertius (5.77-80).

There is little doubt that it was his dynamic role as the first director of the Library and Mouseion that firmly established their international renown.

Photo: A leaf of an open papyrus codex

Regarding the collection of books, we learn from the oldest surviving text, which is the Letter of Aristeas, that it was conceived as a universal library (9-10) "Demetrius… had at his disposal a large budget in order to collect, if possible, all the books in the world; …to the best of his ability, he carried out the king's objective."

The same claim is reiterated more than once: Irinaeus (ibid.) speaks of Ptolemy's desire to equip "his library with the writings of all men as far as they were worth serious attention". Much later, a medieval text, most probably also derived from Aristeas, repeats the same allegation (Tzetzes, Proleg. p.31. Mb 8 f.). Undoubtedly, however, the larger amount was in Greek, in fact, judging from the scholarly work done in Alexandria, we have the impression that the whole corpus of Greek literature was amassed in the Library.

Among the major acquisitions was the collection which our sources call " Aristotle's books", concerning which we have two conflicting accounts.

According to one version, Athenaeus (I.10) asserts that Philadelphus purchased the books for a large sum of money; whereas Strabo (12.1.54), following another tradition, reports that Aristotle's books passed on in succession to Neleus, and were subsequently sold by his family to the great book collector, Apellicon in Athens, whence they were later confiscated by Sulla in 86 BC. who carried them away to Rome.

Should there be any veracity in these accounts, a solution to their conflicting contents is perhaps to suggest that they deal with two different things.

The one reported by Athenaeus, could be concerned with the collection of

books from 'Aristotle's library' amassed at his school in Athens which

Philadelphus was able to purchase during the time when his former tutor,

Straton was head of the Lyseum. This suggestion may find support in

Strabo's statement that Aristotle ranked "first as a book collector and

taught the kings of Egypt the institution of a library" (13.1.54).

Strabo's account, on the other hand, is apparently concerned with the personal writings of Aristotle and Theophrastus, which were bequeathed to Neleus and eventually confiscated by Sulla. Plutarch's remark gives weight to this understanding when he says that the Peripatetics did not possess the original texts of Aristotle and Theophrastus, because the legacy of Neleus had "fallen into idle and base hands" (Plu., Sulla 29).

The wide-spread belief that Aristotle's library was deposited in Alexandria, gave rise in the Middle Ages to the credence that Aristotle himself may even have taught at that city.3

Photo: Mummy portrait of Hermione, grammatike (woman of letters)

There were fabulous stories that circulated concerning the lengths to which the Ptolemies would go in their avid hunt for books.

One of the methods was to search every ship sailing into the harbour of Alexandria, if a book was found, it would be taken to the library where the decision would be taken whether to return it, or confiscate it and replace it by a copy made on the spot, with an adequate compensation, to the owner.

Books acquired in this manner were designated, according to Galen "from the ships" for identification of the origin (Galen, Comm. in Hippocr. Epidem. III.pp.4-11).

Another notorious story that reveals the unscrupulous means to which the Ptolemies would go in order to acquire original texts, is the one told whereby the original manuscripts of the works of the great dramatic poets, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides were obtained:

The precious texts were safe-guarded in the Athenian state archives and were not allowed to be lent out. Ptolemy III however was able to persuade the governors of Athens to permit him to borrow them in order to have them copied. The enormous sum of fifteen talents of silver was deposited in Athens as a pledge for their safe restitution. The King thereupon kept the originals and sent back copies, willingly forfeiting his pledge (Galen, In Hippocr. De Nat.Hominis, I. pp.44 ff., = Corpus Medis. Graec. V.9.1, p.55).

Beside these irregular methods, books were usually purchased from different places, especially from Athens and Rhodes, the largest book marts at the time (Athen. I, 10). Different versions of the same work would occasionally be bought as, for example, those of the Homeric text which came "from Chios", "from Sinope" and "from Massalia".4

The Egyptian Section of the Alexandria Library

As already stated, the Library was intended to be universal, comprising the writings of all nations. Foremost among non-Greek works, was no doubt the Egyptian section.

The founder of the Dynasty must have realised that a thorough knowledge of the country and its inhabitants was necessary for the establishment of his monarchy on a sound basis. He therefore encouraged Egyptian priests to accumulate records of their past tradition and heritage and to render them available for use by Greek scholars and men of letters whom he invited to reside in the country.

Diodorus provides a description of what took place at that early stage in the life of the Library: "Not only," he reports, "did the priests of Egypt render accounts of their records, but many also of the Greeks who went up as far as Thebes, under Ptolemy son of Lagos, composed histories of Egypt, one of whom was Hecataeus (of Abdera)" (Diod. I. 46.8=F.Jacoby, FGH, 3a, 264 F 25, p.33)

In confirmation of this statement, two names immediately occur to the mind, Manethon and Hecataeus of Abdera.

Manethon is the well-known Egyptian high priest of Heliopolis, well versed in the lore of his native land, whom Ptolemy I consulted on the adoption of Sarapis as the official deity for the new dynasty. His other, more lasting task was to collect information from the 'sacred records' and compile a complete Egyptian history in Greek (Aegyptiaca), which he dedicated to Ptolemy II (Diod.I.87.1-5 ; 88.4).

Due to his command of the Egyptian language and knowledge of the history of Egypt, his complete work would have been of unique value; unfortunately it has only survived in excerpts. Although his long recital on the episode of the Hysksos and Moses, is believed to have been much interfered with, yet his long chronological lists of the Egyptian dynasties and kings is of great value as is his division of the Pharaohs into thirty dynasties and three major periods which is still adopted by modern Egyptologists. 5

As for Hecataeus, he was one of the Greek writers invited by Ptolemy I to

reside in the country and write its history. His "Aegyptiaca" has

not survived in its entirety but long excerpts from it were incorporated

into 'Histories' of Diodorus.

As for Hecataeus, he was one of the Greek writers invited by Ptolemy I to

reside in the country and write its history. His "Aegyptiaca" has

not survived in its entirety but long excerpts from it were incorporated

into 'Histories' of Diodorus.

In describing his own method of writing history, Hecataeus makes the following claim, "As for the stories invented by Herodotus and certain writers in Egyptian affairs, who deliberately preferred to the truth the telling of marvellous tales and the invention of myths for the amusement of their readers, these I shall omit, and we shall set forth what appears in the written records of the priests of Egypt and had passed our careful scrutiny" (ap. Diod. I. 69. 7).

We need not take this criticism too literally since Hecataeus adopted much of Heridotus' account in its main outline while making his own contributions only in certain matters of detail which were probably derived from the sacred records, as well as from his own personal observations.

Recent studies have revealed certain points in which Hecataeus differed from or even corrected Herodotus.6 In dealing with the aspect of the Egyptian scientific activity, he highly praised the efforts of the Egyptian scientists in particular in the field of astronomy where he asserts that, "to this day, they have preserved records concerning each of the stars over an incredible number of years….. and as a result of their long observations they have prior knowledge of earthquakes and floods, of the rising of comets….etc." (ap. Diod. I. 81. 4-5).

Admiration for Egyptian astronomy by the Greeks was not limited to Hecataeus alone; mention has been made of Eudoxus of Cnidus, who studied astronomy in Egypt shortly before Alexander's conquest.

Photo: A papyrus roll of Homer's Iliad

The Papyri: Evidence of Greek and Egyptian Scientific Interchange

The papyri provide us with evidence that this aspect of interchange still continued after Alexander and coincided with the founding of the Library.

The Greek Hibeh papyrus no.27 which dates from 301-298 BC., has as its

main subject, a detailed calendar from the Saite nome in the Delta; and it

is prefaced by an introduction, presumably in the epistolary form, in

which the compiler informs us that he "spent five years in the Saite as

disciple to a wise man from whom he learned a great deal."

He goes on to say that the wise man explained and indicated all the facts in practice, with the use of a cylindrical stone instrument which Hellenes call "gnomon". Furthermore, the wise man expounded that the sun had two courses, one dividing night and day and the other winter and summer.

At this point the compiler adds a remark on the method with which astronomers and sacred scribes (Hierogrammateis) could fix the setting and rising of the stars and thereby could keep most of the festivals annually on the same day without alteration.

There is little doubt but that the wise man referred to was an Egyptian priest versed in astronomy. Furthermore, the identification in the text of the Greek word 'gnomon' with the Egyptian stone instrument for the measuring of time, is an indication that translation into Greek was active at the time of the founding of the Library. 7

One might add that similarities between parts of the Hibeh papyrus and an astronomical treatise known as "Ars Eudoxi" which has survived in Papyrus de Paris no.1 (of the 2nd century BC.), suggest that both were derived from a much older prototype.

In addition, we know of a Ramesside calendar8 that has survived in a hieratic papyrus which employs the same system for measuring time on the basis of an equinoctial hour (of a constant duration), there is reason, therefore, to believe that the Ars Eudoxi and the Saite calendar were following an old Egyptian tradition.

Photo: A private letter from Oxyrhynchus

In addition to the acquisition of the bulk of Greek literature and a full corpus of Egyptian records, there is evidence that the new Library also incorporated the written works of other nations.

Almost simultaneously, at the beginning of the third century BC., similar work was taking place in the Seleucid kingdom, where a Chaldaean priest named Berossos wrote a history of Babylonia in Greek. His book immediately became known in Egypt and was probably used by Manethon (Maneth.fr.3,ed. Waddell).

Oriental religions seem to have had a great attraction and according to Pliny (H.N.30. 3-4) a voluminous book - in two million lines - on Zoroastrianism was written by Hermippus, a pupil of Callimachus (Diog. Laert., Proem. 8 speaks of a book "On the Magi" by Hermippus). Such an ambitious undertaking would imply that detailed material on the Persian Mazidan faith was available in the Alexandria Library.

Buddhist writings would also be available as a consequence of the exchange of embassies between Asoka and Philadelphus (Corpus Inscript. Indic. I. P.48, ed. E. Hultzsch). Intellectual curiosity as well as academic interest no doubt motivated scholars to study and write about oriental and ancient religions, but more crucial reasons lay behind the translation of the Pentateuch of the Old Testament. Such a translation from the Hebrew into Greek, was a practical necessity for the large Jewish community in Alexandria, already Hellenised by the end of the third century BC. The obviously fictitious presentation of the translation of the Septuagint as related in the Letter of Aristeas is no longer accredited, in actual fact, the translation was executed piecemeal during the third and second centuries BC.9 But the important point here, is that such an achievement was rendered possible in Alexandria owing to the abundance of research material available in the Library.

The Septuagint has survived as the most valuable work in the history of all translations and it continues to be indispensable to all biblical studies.

It appears that from the beginning, the combination within one project between Mouseion and Library under the dynamic direction of Demetrius of Phalerum was most advantageous.

In so far as the Library was required to satisfy the needs of scholars at the Mouseion, this association helped the Library to develop into a proper research centre.

Furthermore, their location within the grounds of the royal palaces,

placed them under the direct supervision of the kings (Letter of Aristeas)

and this situation was favourably reflected in the rapid growth of the

collection of books. Half a century had hardly passed after its foundation

in c. 295 BC., when it was felt that the premises of the 'Royal Library'

was not large enough to contain all the books that had been acquired, and

that it was found necessary to establish an offshoot that could house the

surplus volumes.

This branch library was incorporated into the newly built Serapium by Ptolemy III, Euergetes (246-221 BC.) which was situated at a distance from the royal quarter in the Egyptian district, south of the city. 10

As regards the total number of books in the Library various figures were reported at different times:

The earliest surviving figure under the first two Ptolemies is reported as "more than 200,000 books" (Aristeas, 9-10) whereas the medieval text of Tzetzes, derived from an ancient source, mentions "42,000 books in the outer library; in the inner (i.e. Royal Library) 400,000 mixed books, plus 90,000 unmixed books"

A still higher estimate of 700,000 was reported between the second and fourth centuries AD. (Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 7.17.3; Amm. Marcellinus 22.16.13).

An interesting passage in Galen, reveals the existence of an intricate system of registration and classification. The information recorded on each book revealed not only the title of the work and the names of its author and editor of the text, but also the place of its origin, the length of the text (i.e. number of lines) and whether the manuscript was mixed (containing more than one work) or unmixed (one single text only) (Galen, Comm. Hipp. Epidem. III.4-11).

An early example of the title and number of lines at the end of a text has been found in a papyrus roll of Menander's Sicyonius of the third century BC.11

It is worth noting that a scribe's pay was rated according to the quality of writing and the number of lines. A papyrus of the second century AD. gives the rates "for 10,000 lines, 28 drachmae…. For 6,300 lines, 13 drachmae."

In an attempt to standardise costs and wages throughout the Empire, Diocletian rated a scribe's pay as follows : "to a scribe for the best writing, 100 lines, 25 denarii; for second quality writing 100 lines 20 denarii; to a notary for writing a petition or legal document, 100 lines, 10 denarii." 12

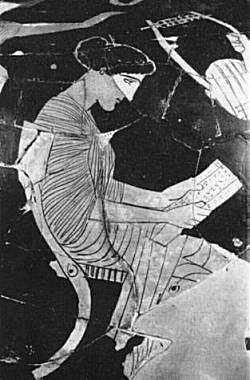

Photo: Sappho reading her book (From an Athenian vase 5th c. BC)

We should not end this chapter without briefly mentioning the well-known work of Callimachus regarding the Alexandria Library.

So far we have seen that an up-to-date register of the books was available for the use of readers, still it was thought necessary to compose a critical appraisal of this unique collection of books, in other words, a bibliographical survey of the contents of the Library 'in every field of learning'.

Such a tremendous undertaking was entrusted to Callimachus of Cyrenae, who was known for his encyclopaedic knowledge and erudition.

The result was the Pinakes.

The work in its entirety has not survived except for a few fragments, which attest to the following divisions:

rhetoric, law, epic, tragedy, comedy, lyric poetry, history, medicine, mathematics, natural science and miscellanea.13

Under each division, individual authors were arranged in alphabetical order; and each name was followed by a short bibliographical notice and a critical account of the author's writings.14

It seems that the Pinakes proved indispensable to scholars all over the Mediterranean and it immediately became a model for future works of the same kind.15

We can even trace its influence down to the middle ages, to its brilliant Arabic counterpart of the tenth century, Ibn-Al-Nadim's Al-Fihrist, or Index, which has fortunately reached us intact.

It was mainly due to the great Alexandria Library that scholarship in Alexandria flourished and continued to flourish, for it was based upon thorough study and an understanding of the value of a past heritage that was deemed worthy of preservation.

Vitruvius, in the first century (de Arch. VII. praef. 1-2) expresses the appreciation and gratitude felt by subsequent generations for the work of the 'predecessors' in preserving for the 'memory of mankind', the intellectual achievements of earlier generations.

"Hence," he adds, "we must render to them more than moderate thanks, indeed the greatest, because they did not let all go in jealous silence, but provided for the record in writing of their ideas in every kind."

Photo: Scribes writing on wooden tablets. An author who wanted to make ten copies of his work dictated to ten scribes at the same time.

Appendix 1 -- The Contents of the Alexandria Library

Considering that modern scholars estimate that surviving classical works do not exceed one tenth of the original legacy, it is inconceivable that one can form even a vague idea of the contents of the ancient library in its entirety . Yet with the help of surviving literary tradition as well as with papyrological finds, one may tentatively suggest the following brief list as a possible indication of the contents of the ancient Alexandria Library:

A. Greek:

I Poetry: Homer, Hesiod, Sappho, Anakreon, Simonides, Pindar, Bacchylides, Callymachus, Apollonius, Theocritus, Aratos.

II Drama: Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes, Menander, Straton (com.).

III Criticism: Zenodotus, Aristophanes (of Byz.), Aristarchus (of Samothr.), Aristonicus.

IV Philosophy: Pre-Socratics (e.g. Anaxmander, Parmenides, Xenophanes, Heraclitus), Plato, Aristotle, Theophrastus, Zeno, Epicurus, Pyrrhon, Panaetius, Philon (Alex.), Apollonius (of Tyana), Plotinus.

V History: Hecataeus, Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Ephorus, Hecataeus (Abdera)...

VI Science: Original exploration reports, Eudoxus (Cnid.), Euclid, Aristarchus (Samos), Straton (Lampsacus), Eratosthenes, Megasthenes, Patroclus, Archimedes, Apollonius (Perga), Hipparchus (Nicaea), Cl. Ptolemy, Theon, Hypatia.

VII Medicine: Corpus of Hippocrates, Herophilus (anatomy), Erasistratus (veins), Callimachus (med.), Sarapion, Heracleides (Tarentus), Rufus, Apollonius Mys, Galen.

B. Non-Greek:

Egyptian sacred records, Manethon, Egyptian manuals on astronomy, instruments, medicine; Berossos (Babylonia), Persian religion, Hebraic scriptures, Buddhist writings….

Appendix 2 -- The End of the Library

The persistent question that is invariably asked when mention is made of the Alexandria Library, is how the greatest collection of books in the ancient world came to an end. To cut a long story short, we know that there were two principle centres wherein the books were kept: the Royal Library, located close to the harbour within the precincts of the royal palaces, and the Daughter Library, incorporated in the Sarapeum, south of the city.

The Royal Library

The Royal Library was an unfortunate casualty of war. In 48 BC., Caesar

found himself involved in a civil war between Cleopatra and her brother

Ptolemy XIII. Caesar sided with Cleopatra and was soon besieged by land

and sea by the Ptolomaic forces. He realised that his only chance lay in

setting fire to the enemy fleet and it was by this drastic measure that he

managed to gain the upper hand. But the fire, in the words of Plutarch,

spread from the dockyards and destroyed the "Great Library" (megalé

bibliotheke) [ Caes. 49].

The Daughter Library

As regards the Daughter Library, it continued to function throughout the

Roman period under the protection of the Sarapeum. Nevertheless, with the

end of paganism and the ascendancy of Christianity in the fourth century,

the Sarapeum lost its sanctity. In 391, when the Emperor Theodisius

ordained the destruction of all pagan temples, contemporary eyewitnesses

assert that the Sarapeum, together with all its contents, suffered

complete annihilation. [Rufinus, H.E. 2. 23-30; Eunapius, vit. Aedesii,

77-8; Socrates, H.E. 5.16.].

The Arab Conquest

Thus, when the Arabs conquered Egypt in 642, the Alexandria Library no

longer existed. It is noteworthy that no historians of the conquest,

whether Byzantine or Arab, ever mention any accident that could have

occurred to the Library. It was not until six centuries later, during the

time of the Crusades, when all of a sudden a story emerges, claiming that

the Arab general Amr Ibn Al-As, had destroyed the books by using them as

fuel for the baths! [Ibn Al-Quifti 354].

Modern scholarship has proved beyond any doubt that this story was a twelfth century fabrication, resulting from war conditions during the Crusades. [For a full treatment of the subject, cf. A.J. Butler, The Arab Conquest of Egypt, 400 ff.; M. El-Abbadi, Life and Fate of the Ancient Library of Alexandria, 136-166].

- G. Toomer, "Eudoxus", OCD 3rd ed. (1996); O.Neugebaur, The Exact Sciences in Antiquity, 2nd ed. Dover Pub.,N.Y. (1969) 151.

- The point has repeatedly been discussed, cf. M.El-Abbadi, Life and Fate of the Library of Alexandria, Paris (1992) 79 ff.; L. Canfora, La bibliotheque d'Alexandrie et l'Histoire des Textes, Cedopal, Universite de Liege (1992) 11 ff.

- Abdellatif Al-Baghdady, Al-Ifada wa'l I'tibar (Voyage to Egypt) p42; Maqrizi, Topography, apud D. E. Garcia de Herreros, Quatre Voyageurs Espagnols a Alexandrie, p.27

- On the so-called 'city versions' of Homer, see R. Pfeiffer, History of Classical Scholarship, Oxford (1968) 94, 110,139; P.M. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria, Oxford (1972) I.328, II.483 n.163.

- W.G. Waddell, Manetho, The Introduction (Loeb).

- Christian Leblanc, ' Diodor, Le Tombeau d'Osymandyas et la Statuaire du Ramesseum', Melange Gamal-Eddin Mokhtar, ed. Par Paule Posener-Krieger, IFAO, 97, Le Caire (1985) 69-82; S.M. Burstein, ' Hecateus of Abdera's History of Egypt' Life in a Multi-Cultural Society, ed. By J.H. Johnson, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilizations, no. 51, Chicago, Illinois. (1992) 45-9.

- Theophrastus, almost a contemporary of the Saite calendar, is known to have visited Egypt and used the same word 'gnomon', in the sense of water-clock: Athen.2.42 b; cf. W. Capelle, 'Theophrast in Aegypten', Wien. Stud. 69 (1956) 173-180

- J. Cerny, The Origin of the Name of the Month Tybi, Annales du Services des antiques de l'Egypte, 43 (1943) 173-181

- Luciano Canfora, Il Viaggio di Aristea, Bari, Laterza (1996); A. Pelletier, La Lettre d'Aristee a Philocrate, Source Chretiennes, 89 (1962); cf. V. Tchericover, Corpus Papyrorum Judaicarum, I. pp. 30 f.

- This step was traditionally attributed to Ptolemy II, see Tzetzes, Proleg. p.31 Mb 8 ff. ; for the foundation plates of the Sarapium, A. Rowe, The Discovery of the famous Temple and Enclosure of Sarapis of Alexandria , Cairo (1946) 1-10.

- Menander, Sycionius, ed. A. Blanchard et A. Botaille, recherches de papyrologie, 3 (1964) 161 L P. Sorb. 2272, col.XXI, p.13; also observe Diogenes Laertius who repeatedly states the total number of lines of an author, e.g. IV.5, Speusippus, 43,475 lines; IV.14 Xenocrates, 224,239 lines, V.27 Aristotle, 445,270; Theophrastos, 232,800 lines.

- B. M. Pap. 2110 (II A.D.) ed, H. I. Bell in Aegyptus 2 (1921) 281 ff.; Edict. Of Diocl., col. VII, 29-41.

- R. Pfeiffer, Hist. Class. Schol. 127-133.

- Frag. No. 447, in R. Pfeiffer, The Pinakes Fragments.

- P. Oxy. 1367; Athen. 408 E.

Bibliotheca Alexandrina--The revival of the Library

Alexander the Great's dream of unifying the world sparked the idea of constructing a great library which would gather the cultures and civilisations of the whole world. The location of this great library was Alexandria, Egypt, at the crossroads of the three continents of Asia, Africa and Europe. In this historical moment, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina was built on a site near the famous Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The Egyptian government and UNESCO are keen on reviving the role that the Ancient Library of Alexandria played in advancing knowledge, scholarship and the cultural development of Egypt and the Mediterranean area. To this end a new library is being built in Alexandria. Construction began in 1995 and the inauguration of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina is due to take place in 1999.

Apart from the main Library, the complex will include a Library for the

Blind, a Young People's Library, the Alexandria Conference Centre, a

Science Museum, a Planetarium, the International School of Information

Studies (ISIS), a Calligraphy Museum, a Restoration and Conservation

Laboratory and the Hall of Fame.

Objectives: 1) The Revival of the Ancient Library of Alexandria Project aims at building a universal modern public research library to be a centre of culture, science and academic research.

2) The Library is to provide both the national and international communities of scholars and researchers with unique collections and facilities focusing on Alexandrian, Egyptian, ancient and medieval civilisations as well as on contemporary disciplines. The Library shall also have valuable collections of science and technology resource materials to help the socio-economic and cultural development studies on Egypt and the region.

3) The Bibliotheca Alexandrina shall sponsor intensive studies on the historical and contemporary cultural heritage of the region.

Location:

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina lies alongside the University of Alexandria

Faculty of Humanities campus in Chatby and overlooks the Mediterranean Sea

along a substantial portion of its northern frontage.

At Selsela, it is almost the same site of the ancient library-museum complex within the Royal Quarter, in the district then known as Brocheum, where a few remains of the Graeco-Roman civilisation were recently uncovered and later will be displayed in the Library museum.

At the panoramic vista across the circular Eastern Port stands the old Mameluke Citadel of Qait Bey, built in 1480 on the site of the famous Pharos Lighthouse.

The information above is provided by the General Organisation of the Alexandria Library (G.O.A.L.)

Visit these sites to learn more about the Bibliotheca Alexandrina and UNESCO involvement in the new Alexandria Library.