Alexandria and the Mediterranean in Classical Times

By Dr. Lutfi Abdul-Wahhab Yehya, University of Alexandria, Egypt

Copyright © Hellenic Electronic Center and Dr. Lutfi Abdul-Wahhab Yehya (author) 1998. All rights reserved.

The role of Alexandria in the Mediterranean | International Trade | Scholars and Scholarly Thought | Religion and Religious Thought | Bibliography

Among the cities and ports literally strewing the shores and islands of the Mediterranean, only a few could claim a particularly active, long and many-faceted interaction with the flow of history witnessed by that sea. One of the leading instances in this respect is Alexandria, the city founded by Alexander the Great in 331 B.C. through connecting Rhacotis, a village - or in some opinions a small town - on the northern shore of Egypt and Pharos, an island that lay parallel to the mainland.

The city, the foundation ceremony of which took place on 25th of the

Egyptian month of Tybi (20th January), was intended, among other things,

to be the connecting link between Alexander's kingdom in Macedonia and

Greece which lay under his enforced hegemony, on the one hand and the

eastern empire which he was in the process of acquiring at the time on

the other. The final unity of the two regimes under his sway marked the

turning point of a new era. The centre of what may be termed the

historical gravity which had rested for a millennium in the Syrian

plains and highlands, the battlefields of the contending eastern

empires, had now shifted to the eastern part of the Mediterranean - the

central point between East and West - thus presenting a suitable

atmosphere for an active role for any city in the area that might have

or acquire the attributes suited to the requirements of the age.

The city, the foundation ceremony of which took place on 25th of the

Egyptian month of Tybi (20th January), was intended, among other things,

to be the connecting link between Alexander's kingdom in Macedonia and

Greece which lay under his enforced hegemony, on the one hand and the

eastern empire which he was in the process of acquiring at the time on

the other. The final unity of the two regimes under his sway marked the

turning point of a new era. The centre of what may be termed the

historical gravity which had rested for a millennium in the Syrian

plains and highlands, the battlefields of the contending eastern

empires, had now shifted to the eastern part of the Mediterranean - the

central point between East and West - thus presenting a suitable

atmosphere for an active role for any city in the area that might have

or acquire the attributes suited to the requirements of the age.

Nor did Alexander's premature death alter anything on this score. Rather

than suffering a regression, the new shift was enhanced by the rise of

the three main Hellenistic monarchies, the Antigonid, the Seleucid and

the Ptolemaic, which flanked the Eastern Mediterranean on its three

sides. During the protracted struggle among the new powers for supremacy

in the area, the Ptolemies spared no effort from the very beginning of

their rule, to turn Alexandria, which soon became their capital, into

the first city and port in the Mediterranean in every respect and in

every conceivable manner - thus provoking the atmosphere in which

Alexandria would play its role in the history of the Mediterranean, not

only at the time of the Ptolemies, but long after their ruling dynasty

had disappeared.

The aspects of this role, as might be expected, were many and various. At times they were greatly positive, at others Alexandria looked more like being involved in a role, but in all cases what took place was outstandingly, sometimes fatefully, singular. This brief survey can, of course, accommodate no more than the general outlines of some of these aspects.

Photos: (top) A piece of mosaic found at Tell Temai near Sinbelaween in 1918. (Graeco-Roman Museum, Alexandria) Interpretation I: A portrait of Queen Berenice II, wife of Ptolemy III "Eurgetes I", represented wearing military garbe, holding a sail and wearing a cap in the shape of a warship as a symbol of control over the Mediterranean Sea. Interpretation II: The the city of Alexandria represented in the shape of woman wearing a head-dress in the shape of a ship, symbolising the role of Alexandria in the Mediterranean. (bottom) Mosaic depicting a marine city, possibly Alexandria, personified as a woman. (Graeco-Roman Museum, Alexandria)

A vital weapon almost incessantly used by the new rivals of the Hellenistic period lay in the field of international trade. In his unrelenting efforts to win first place for his chief port, Ptolemy I Soter, the founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty, assigned to Sostratos, who hailed from the small Aegaean island of Cnidus, a task hitherto unprecedented in the history of the region - namely the building of a lighthouse to provide a safe way to ships approaching the port of Alexandria at night.

The magnitude of the project could be gauged by the fact that the

building, which was started about 290 B.C., lasted some ten years before

it was finally completed under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The

light projected from its uppermost part reached over 300

stadia or about 50 metres into the sea - a sure outcome of

putting to use the scientific specialisation which had started earlier

at the Lyceum

of Athens and was later to reach its climax in the research halls of the

Mouseon of Alexandria.

The magnitude of the project could be gauged by the fact that the

building, which was started about 290 B.C., lasted some ten years before

it was finally completed under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The

light projected from its uppermost part reached over 300

stadia or about 50 metres into the sea - a sure outcome of

putting to use the scientific specialisation which had started earlier

at the Lyceum

of Athens and was later to reach its climax in the research halls of the

Mouseon of Alexandria.

That the lighthouse, or the Pharos - as it was called after the

name of the former island where it finally stood - greatly helped in

enhancing trade activity in the Mediterranean , must have been

abundantly clear to the classical authors. Centuries after its

completion, they could still express, in more ways than one, their

fascination both by the building and its components and by the services

it rendered to trade.

Sometime after his stay in Alexandria in c.25-4 B.C., Strabo talks in

his

Geography (XVII, 11) of its lighthouse and the singular service

it offered to the ships during their nocturnal approach to the eastern

harbour or the 'Great harbour' of Alexandria. Although Plinius the

elder, contrary to his habit of lengthy descriptions talks only briefly

about the Alexandrian Pharos in his "Historia Naturalis"

(XXXVI, 18) - only understandable in view of Strabo's detailed

description more than half a century earlier - he takes particular care

to describe it as the prototype of its genre.

Sometime after his stay in Alexandria in c.25-4 B.C., Strabo talks in

his

Geography (XVII, 11) of its lighthouse and the singular service

it offered to the ships during their nocturnal approach to the eastern

harbour or the 'Great harbour' of Alexandria. Although Plinius the

elder, contrary to his habit of lengthy descriptions talks only briefly

about the Alexandrian Pharos in his "Historia Naturalis"

(XXXVI, 18) - only understandable in view of Strabo's detailed

description more than half a century earlier - he takes particular care

to describe it as the prototype of its genre.

Suetonius, writing about A.D. 120, follows suit; when he talks about the

lighthouse built in Ostia under the reign of Claudius and the guidance

it offers to the ships coming into its harbour at night (De Vita

Caesarum, Claudius, 20) he immediately likens it, in this respect, to

'the

Pharos of Alexandria' - thus setting the Alexandrian lighthouse

as an ideal never to be forgotten.

Suetonius, writing about A.D. 120, follows suit; when he talks about the

lighthouse built in Ostia under the reign of Claudius and the guidance

it offers to the ships coming into its harbour at night (De Vita

Caesarum, Claudius, 20) he immediately likens it, in this respect, to

'the

Pharos of Alexandria' - thus setting the Alexandrian lighthouse

as an ideal never to be forgotten.

However, the full Mediterranean dimension of the Alexandrian trade had

developed long before the classical authors displayed their fascination

by the Pharos. A papyrus dating back to the middle of the

second century B.C. (Preisigke, Sammelbuch, 7169) presents a contract

between a number of businessmen forming an international company with

the purpose of conducting commercial transactions. Despite the mutilated

condition of the document, the names of seven members of the company

could be read, representing six nationalities from the Mediterranean

region.

However, the full Mediterranean dimension of the Alexandrian trade had

developed long before the classical authors displayed their fascination

by the Pharos. A papyrus dating back to the middle of the

second century B.C. (Preisigke, Sammelbuch, 7169) presents a contract

between a number of businessmen forming an international company with

the purpose of conducting commercial transactions. Despite the mutilated

condition of the document, the names of seven members of the company

could be read, representing six nationalities from the Mediterranean

region.

Strabo (XVII,I,13) was obviously referring to the same dimension when he called Alexandria, towards the end of the last century B.C., 'the greatest emporium of the inhabited world'. Over half a century later we learn from the unknown writer of the Periplus Maris Erythraei, a guidebook written for the benefit of merchants and seamen, that Alexandria had become by then, the central post for exchange of overseas trade ( Periplus, 26). This would involve, no doubt, the Erythrayean as well as the Mediterranean seas. This is clear from what Josephus tells us (Bell. Iud.,IX,615) when he talks about Alexandria about two decades later, referring to its harbour 'from which the surplus of the local products is distributed to every quarter of the world'.

Photos: Sections taken from a mosaic depicting harbour scenes supposed to be Alexandria from the 3rd Century. AD. Tuledo, Spain.

Scholars and Scholarly Thought

As a seat of learning, Alexandria was no less positively Mediterranean-orientated. Out of the librarians of the famous library of ancient Alexandria - and they were eminent scholars and no mere civil servants - a number came from the various shores of the Mediterranean.

From a papyrus found at Behnasa in Upper Egypt (

P.Oxy. X,1214, col.II), containing the names of six of these

librarians, only two are Greeks from Egypt. The other four were :

Zenodotus of Ephesus, who was the first scholar to establish a critical

text of the two Homeric epics, Eratosthenes of Cyrene, the geographer

who tried with a great deal of success to measure the circumference of

the earth depending on astronomical data and geographical observation -

the final result differing by a matter of only 400 kilometres from its

length according to our present state of knowledge. The third of theses

scholarly librarians was Aristophanes of Byzanteum who edited excellent

texts of the classical poets and other authors up to the time of Plato.

And the fourth was Aristarchus, another editor, whose special field was

poets from Homer to Pindar.

From a papyrus found at Behnasa in Upper Egypt (

P.Oxy. X,1214, col.II), containing the names of six of these

librarians, only two are Greeks from Egypt. The other four were :

Zenodotus of Ephesus, who was the first scholar to establish a critical

text of the two Homeric epics, Eratosthenes of Cyrene, the geographer

who tried with a great deal of success to measure the circumference of

the earth depending on astronomical data and geographical observation -

the final result differing by a matter of only 400 kilometres from its

length according to our present state of knowledge. The third of theses

scholarly librarians was Aristophanes of Byzanteum who edited excellent

texts of the classical poets and other authors up to the time of Plato.

And the fourth was Aristarchus, another editor, whose special field was

poets from Homer to Pindar.

Nor did all the scholars of the Mouseon, the ancient university

of Alexandria come from that city or elsewhere in Egypt. A great many of

them were invited from wherever they could be found in the Mediterranean

region, to teach or conduct their research work. Among these we can mane

such scholars as Hipparchus the astronomer who came from Nicia and

Archimedes of Syracuse, the mathematician famed among other things, for

his theory on floating bodies. Another of these Mouseon lights was

Herophilus of Chalcedon, the anatomist and surgeon whose school - or

'house' as it was called - acknowledged the dissection of bodies as a

basis for conducting their medical research. Philinus of Cos, a pupil of

Herophilus was yet another of those scholars. He started a rival

'empirical' school to his master's, relying on therapy, collected

experience and reaching conclusions through analogy as well as paying

attention to factors which evidently influenced illness.

One last instance of the Mediterranean orientation of the Alexandrian Mouseon, is the case of Plotinus, the real founder of Neo-Platonism. Born in Lycopolis (modern Assiout) in 205 A.D., he moved to Alexandria at the age of 28 where he studied philosophy under Ammonius Saccas for eleven years before he finally settled at Rome. There he became the centre of an influential circle of intellectuals which included men of the world and men of letters, besides professional philosophers such as Amelius and Porphyry, the Syrian-born philosopher who became Plotinus' devoted disciple. There he conducted his seminars and gave the last shape to the ideas which he first developed in Alexandria - and which were collected and published post mortem by Porphyry.

Photos: (top) Funerary stele depicting a temple (Graeco-Roman Museum, Alexandria); (bottom) Marble stele depicting a blind man playing the lyre (Graeco-Roman Museum, Alexandria).

Religion and Religious Thought

Another sphere where interaction between Alexandria and the Mediterranean region was particularly active was that of religion and religious thought. Before dealing with this aspect, however, it might perhaps be in order to mention the role played by Alexandria in this respect was in fact, a new phase on a course which had already started between Egyptian and other shores of the Mediterranean. We learn from Plato's dialogues, for instance, that the cult of Ammon was recognised by the Athenians at an earlier date than the time of the Peloponnesian wars ( Alcibiades II, 148-9) and that this deity's oracle was held in awe in the same way as those at Dodona and Delphi (Nomoi, 738).

It is not surprising, therefore, that various areas in the Mediterranean

region should continue to adopt a number of Egyptian cults emanating

from Alexandria after its foundation. Two of these cults, particularly

connected with the city were Isis and her consort Sarapis, who formed

with their son Harpocrates (a synonym of Horus) the Alexander Triad. For

reasons outside the scope of the present survey the cults of these two

deities, either singly or as a pair, found their way to the Asian and

European shores of the Mediterranean.

It is not surprising, therefore, that various areas in the Mediterranean

region should continue to adopt a number of Egyptian cults emanating

from Alexandria after its foundation. Two of these cults, particularly

connected with the city were Isis and her consort Sarapis, who formed

with their son Harpocrates (a synonym of Horus) the Alexander Triad. For

reasons outside the scope of the present survey the cults of these two

deities, either singly or as a pair, found their way to the Asian and

European shores of the Mediterranean.

A papyrus (P. Zenon Cairo, I, 59034) dating back to 257 B.C. contains a rather significant letter to that effect, from a certain Zoilus, a citizen of Aspendos in Asia Minor, to Apollonius, supervisor of the financial affairs in Egypt at the time of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. From the letter we learn that while Zoilus was consecrating his time to the service of Sarapis (at Aspendos) to gain his blessings for the work of Apollonius with King Ptolemy (in Egypt), the god used to appear to him in his sleep and bid him go to Apollonius in Alexandria to convey to him the god's warnings to complete a temple and a shrine for him there.

When Zoilus showed some lassitude in effecting the god's bidding he fell ill and again Sarapis appeared to him in his sleep and repeated his warning. At this juncture a friend from Cnidus (an island off the south-western tip of Asia Minor), offered to enforce the required buildings, but this seemed not to satisfy the god, so Zoilus fell ill once more for a few months. At the end of the letter, he asks Apollonius to appease Sarapis by completing the temple and the shrine in question.

Apart from the Eastern shores of the Mediterranean , where we have just

mentioned two of the many centres of the cult of Sarapis, the European

shores of that sea had also adopted this cult as well as that of Isis,

in a rather big way. However, I shall confine myself here to one major

centre in this respect, namely Rome, the city and the state.

The cults of the two deities had already found their way to Rome, partly through Greek sailors, before the middle of the second century B.C.. Their presence was felt to such a degree as to make one of the two consuls pass a decree in 168 B.C., in which he ordered the demolition of their shrine (Valerius Maximus, I, 3-4). Yet despite the fact that their worship was checked more than once and in more than one way, whether under the Republic or at the time of the Empire, the two cults continued to gain ground in both periods and both on the populist and the official score.

Under the first triumvirate (43 B.C.) the cult of Tsis and Sarapis was

officially recognised (Cassius Dio, XLV II, 15). Eight decades

later, during the reign of Caligula (A.D. 37-41), the first state temple

of Isis was erected. In 69 Otho was the first Roman emperor to worship

Isis, setting an example for several later emperors who worshipped

either or both deities. Sometime between the middle of the second and

the middle of the third century Minucius Felix (Octavius, XXII)

could say about Isis and Sarapis, "They were once Egyptian, now they are

Roman deities." Three and a half centuries after the rise of

Christianity, the cult of Isis seems to be still holding its ground in

Rome; in 349 we find Nicomachus Flavius, the Roman consul officially

celebrating the feast of the goddess (Antologia Latina, I, 16).

Under the first triumvirate (43 B.C.) the cult of Tsis and Sarapis was

officially recognised (Cassius Dio, XLV II, 15). Eight decades

later, during the reign of Caligula (A.D. 37-41), the first state temple

of Isis was erected. In 69 Otho was the first Roman emperor to worship

Isis, setting an example for several later emperors who worshipped

either or both deities. Sometime between the middle of the second and

the middle of the third century Minucius Felix (Octavius, XXII)

could say about Isis and Sarapis, "They were once Egyptian, now they are

Roman deities." Three and a half centuries after the rise of

Christianity, the cult of Isis seems to be still holding its ground in

Rome; in 349 we find Nicomachus Flavius, the Roman consul officially

celebrating the feast of the goddess (Antologia Latina, I, 16).

The religious interaction between Alexandria and Rome did not limit itself to the sphere of pagan cults. During the second half of the second century Alexandria and Rome were beginning to take up a new role in the protracted confrontation between pagan and Christian polemists. Since the apostolic times this confrontation had taken the shape of literary wrangling, accusations, explanations.

Although this phase still persisted, a new phase had already begun. Instead of dwelling on these peripheral issues, largely emotional in their nature, matters were taking a new turn. The contenders concerned themselves now with the core and credibility of their respective creeds as a way of life. About 178-80 Celsus, a Greek philosopher advocating the cause of paganism, of which Rome - with its Emperor Cult - was the staunch protagonist, wrote the first comprehensive polemic against Christianity, the Aléthés Logos or True Doctrine. Denouncing Christianity as being based on sheer belief and therefore addressing itself mainly to the blind faith of the ignorant and the uncultured, he depended in his arguments on the reasoning of Greek philosophers and the precedent of wisdom found in the truly inspired Greek poetry.

Two of the Alexandrian Christian fathers, Titus Flavius Clemens, or

Clement of Alexandria, as he is more commonly known, (c.150 - between

211 and 216) who eventually became head of the Catechitical School at

Alexandria before having to leave the city in 202, and Origenes

Adamantius or Origen (185/186 - 252-5), his pupil and successor in his

post, undertook successively to refute Celsus' arguments. Both were

steeped in Greek philosophy and one of them at least, Clement, had a

wide acquaintance with Greek literature and mysteries; and so they set

on their task depending on the same sources as their opponent.

In his Pretrepticus or 'Exhortation', (passim) Clement draws ad lib on Greek poets, dramatists, historians and philosophers to shed the necessary light on his arguments. His approach - abundantly testified by quotations from Homer and Hesiod to Euripides, ideas from Heracleitus and Democritus to Plato, the peripatics and the stoics, and, among others, facts from Herodotus, Thucydides and Xenophon - centres on the fact that the Greek literary, historic and philosophic legacy, rather than constituting an obstacle in the way of a cultivated pagan who wishes to turn to Christianity, was actually a preparation on the way to the ultimate truth contained in the new creed.

Origen followed his master's trend in so far as his object was to expound a way of Christian life. However, while Clement's address was not directed to Celsus per se, but was intended rather as a criticism of pagan ways and pagan thought on the one hand and a presentation of the assets of the Christian creed in the other, Origen's was a direct reply, point by point to Celsus' treatise (Contra Celsum, passim). Again, while both men avoided a directly hostile attitude in dealing with the pagan ideas, Origen was, perhaps more subtle in doing so. While never losing sight of his objective, he would grant a point or two in his opponent's argument , but would always end by proving the Christian standpoint in the light of Greek philosophical reason.

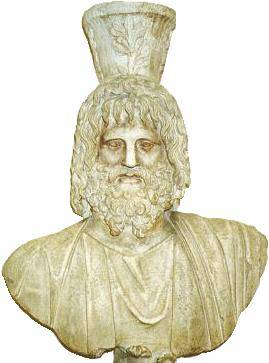

Photos: 1) Bust of the god Serapis with a bushel on his head to indicate a plentiful harvest. (Graeco-Roman Museum, Alexandria); 2) Wooden statue of the god Serapis (Graeco-Roman Museum, Alexandria); 3) Statue of a Ptolemaic Queen depicted as the goddess Isis (Graeco-Roman Museum, Alexandria); 4) Icon of the Apostle St. Mark in Alexandria. (Patriarchate of Alexandria).

- Adam, Jean Pierre, Le Phare d'Alexandrie, in 'Alexandrie Lumiere du Monde Antique' (Les Dossiers d'Archeologie, no.201, 1995).

- El-Abbadi, Mustafa, The Life and fate of the Ancient Library of Alexandria, Unesco Publications, Paris, 19.

- Cahiers d'Alexandrie, Societe Archeologique d'Alexandrie, Alexandria 1964

- Fraser, P.M., Ptolemaic Alexandria, Oxford, 1972.

- Holbl, Gunther, Verehrung agyptischer Gotter im Ausland, lexikon der Agyptologie, VI, Wiebaden, 1986.

- Westermann, William Linn, The Library of Ancient Alexandria, University of Alexandria Publications, Alexandria, 1954.

- Yehya, Lutfi A-W., Alexandria and Rome in Classical Antiquity, a Cultural Approach , in Atti del. I Congresso Internazionale Italo-Egiziano, Roma, 1992.