The Tomb of Alexander the Great

The history and the legend in Greco-Roman and Arab times

By Harry E. Tzalas

Copyright © Hellenic Electronic Center and Harry E. Tzalas (author) 1998. All rights reserved.

Alexander as Myth | Where is Alexander Buried? | Ancient Sources | The Destruction of Alexandria | The arrival of the Arabs | St. Athanasius | The Nabi Danial Mosque | The search continues

Alexander the Great died in Babylon in the summer of 323 BC. In his brief reign he not only conquered the greatest part of the then known world, but brought vast changes to the regions of the empire that he built.

His life and deeds, as well as his death and burial, became a legend for

future generations, far beyond the lands he had conquered. He was

remembered in legend1 from Iceland to China and is still

invoked as their ancestor or patron by tribesmen in Afghanistan.

His life and deeds, as well as his death and burial, became a legend for

future generations, far beyond the lands he had conquered. He was

remembered in legend1 from Iceland to China and is still

invoked as their ancestor or patron by tribesmen in Afghanistan.

In fact, until the Renaissance, it is the legend of Alexander that prevailed, as reliable historical sources were practically unknown.

The legend differed greatly from one region to another and was adapted and merged with pre-existing local traditions.

The legend of Alexander started spreading right after Alexander's death

and overshadowed his real life. Alexander became a mythical figure, a

theme for folk-songs, epics and anecdotes. Even his name was modified or

distorted.

The legend of Alexander started spreading right after Alexander's death

and overshadowed his real life. Alexander became a mythical figure, a

theme for folk-songs, epics and anecdotes. Even his name was modified or

distorted.

Alexander's personality was adapted according to the use each nation or tribe made of the conqueror's fame. He became a local hero. Even the Persians, whose empire Alexander had conquered, made of him a Persian hero, son of Darius.

It seems that the legend of Alexander had its roots in Egypt, was written in Greek and was falsely attributed to Callisthenes. Thus it remained known as the Pseudo-Callisthenes2.

It was translated and rendered in many versions and in many languages spreading all over the Eastern and Western world.

The legend had little in common with the true story of Alexander: The Byzantines made of Alexander a Saint while the Mohammedans include his deeds in the Koran, to mention only two extremes.

There are adaptations of Alexander's Romance in prose and verses, in the Greek language, Latin, Syriac, Armenian, Persian, Arab, Hebrew, Coptic, Ethiopian, Spanish and numerous other languages and dialects. In French, the Romance is known as "la légende" or "la Romance d'Alexandre" and Alexander is one of the gallant knights of Charlemagne, in English it is "the Romance of Alexander", in German "Alexandersage".

The Byzantines transmitted the legend to the Slavs and we have Alexander's Romance in the folklore of the Serbs, Croats, Czechs, Poles etc.

This paper, however, is limited to the history and myth connected with the "last dwelling" of Alexander: his mausoleum, whose splendour and display of wealth were the admiration of historians and travellers for centuries, and still excite the popular imagination.

Photos: Two tapestries. Alexander the Great on his death bed (top); the Persians made a hero of Alexandria the Great (bottom).

Notes:- 1. For the Romance of Alexander see: A. Adel, Le Roman d'Alexandre. Legendaire Medieval, Bruxelles (1955). J.A. Boyle, "The Alexander Romance in Central Asia". Zentralasiatische Studien 9 (1965): 265 and "The Alexander Romance in the East and West", B.J.R.L. 60 (1977): 13 F.W. Cleaves, "An early Mongolian Version of the Alexander Romance", Harv. J. Asiatic Stud. 22 (1922). R. Dankoff, "The Alexander Romance in the Diwan Lughat-Turk", Humaniora Islamica 1 (1973): 233. T. Fahd, La version arabe du Roamn d'Alexandre, Graeco-Arabica, vol. IV (1991), P.M. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria, vol. 1 (1972), 676. I. Friedlaender, Die Chadhirlegende und der Alexanderroman (1913). E. Garcia Gomez, Un Texto Arabe Occidental di la legenda di Alejandro (1929). D. Holton, The Tale of Alexander, the Medieval Greek rhymed version (1974). J. Horowitz, Koranische Untersuchungen (1926), 111-113. J.J. Kazis, Book of the Gests of Alexander of Macedon (1962). M.S. La Du, ed., The Medieval French Roman d'Alexandre, vols. 1-6 (1937-1955). R. Macuch, "Pseudo-Callisthenes Orientalis and the problem of Du l-qarnian", Graeco-Arabica, vol. IV (1991). M. Marin, Legends on Alexander the Great in Moslem Spain, Graeco-Arabica, vol. IV (1991), M.M. Mazzaoui, "Alexander the Great and the Arab Historians", Graeco-Arabica, vol. IV (1991). F. Pfister, Der Alexanderroman, mit vervandten Texten (1978). D.J.A. Ross, Alexander Historiatus (1963). L. Ruggini, "Il Mitto di Alessandro dall'eta Antonina al Medioevo", Athenaeum 43 (1965) : 3. G.V. Smithers, ed., King Alisaunder, vols. 1-2 (1952, 1957). A.M. Wolohojian, The Romance of Alexander, trans. from Armenian (1969).

- 2. R. Macuch, Pseudo-Callisthenes, op. cit.

With the passing of time, a dense veil of mystery has covered the burial of Philip's son, and it has become difficult to distinguish the historical facts from the legend. The legend was first woven in Greco-Roman times, and continued with additions in the Christian period and after the Arab conquest. It can indeed, be said that the legend of Alexander's tomb is still present in today's Alexandria.

Nearly everything related to Alexander's burial has become the subject of

controversy. We have, however, to accept as reliable the story of Diodorus

Siculus that the body was embalmed and that after numerous vicissitudes

and a delay of two years, the funeral convoy started on the long journey

to Egypt. Philip Arrhidaeus, the feeble minded son of Philip II of

Macedonia, who had been chosen by the Macedonian army at Babylon as the

successor of Alexander, was put in charge of all the arrangements

3.

Nearly everything related to Alexander's burial has become the subject of

controversy. We have, however, to accept as reliable the story of Diodorus

Siculus that the body was embalmed and that after numerous vicissitudes

and a delay of two years, the funeral convoy started on the long journey

to Egypt. Philip Arrhidaeus, the feeble minded son of Philip II of

Macedonia, who had been chosen by the Macedonian army at Babylon as the

successor of Alexander, was put in charge of all the arrangements

3.

Was the intended destination the oasis of Siwah, where the oracle of Ammon had confirmed, some years earlier, his divine Lineage? Or was this a trick of Ptolemy Lagos (337-283), who wanted the body of the conqueror to be buried in Alexandria, in order to fulfill the prophecy of Aristander, Alexander's favourite soothsayer, who had predicted "that the country in which his body was buried would be the most prosperous in the world"?

It is difficult to judge. It is, however, reported that when the funeral procession reached Syria, an army was sent by Perdicas to intercept the precious remains and divert the convoy to Aigai in Macedonia.

A battle took place and it is quite possible that the sarcophagus of white

pentelic marble found at Sidon in 1886 and originally attributed to

Alexander, belonged to one of the dignitaries killed in the engagement. It

perhaps contained the body of Ptolemon, who was sent by Perdicas at the

head of an army to take the body and who died in the engagement. This

sarcophagus is now exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of

Constantinople.

A battle took place and it is quite possible that the sarcophagus of white

pentelic marble found at Sidon in 1886 and originally attributed to

Alexander, belonged to one of the dignitaries killed in the engagement. It

perhaps contained the body of Ptolemon, who was sent by Perdicas at the

head of an army to take the body and who died in the engagement. This

sarcophagus is now exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of

Constantinople.

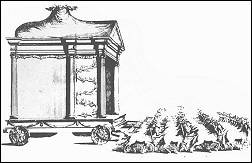

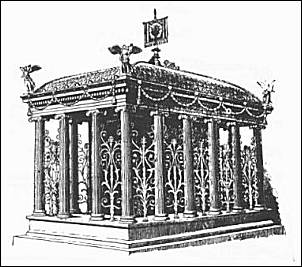

Finally, according to Diodorus, the funeral carriage, a wheeled monument on which the body of the hero was laid, was pulled all the way to Alexandria via Memphis.

An attempt to reconstruct the procession in drawings, based on Diodorus account, was made in the middle of the 18th century by the French Compte de Caylus4.

His life and deeds, as well as his death and burial, became a legend for future generations, far beyond the lands he had conquered. He was remembered in legend1 from Iceland to China and is still invoked as their ancestor or patron by tribesmen in Afghanistan.

His life and deeds, as well as his death and burial, became a legend for future generations, far beyond the lands he had conquered. He was remembered in legend1 from Iceland to China and is still invoked as their ancestor or patron by tribesmen in Afghanistan.

Strabo, Plutarch, Pausanias and other ancient authors mention that it was

in Alexandria that Alexander's body was deposited in a Mausoleum called

the Soma or Sema5, meaning a body or burial in Greek. A gold

sarcophagus and a grandiose building with a great display of wealth were

appropriate to receive the remains of a deified hero, who in his lifetime

had united the Greek and the Oriental worlds.

Strabo, Plutarch, Pausanias and other ancient authors mention that it was

in Alexandria that Alexander's body was deposited in a Mausoleum called

the Soma or Sema5, meaning a body or burial in Greek. A gold

sarcophagus and a grandiose building with a great display of wealth were

appropriate to receive the remains of a deified hero, who in his lifetime

had united the Greek and the Oriental worlds.

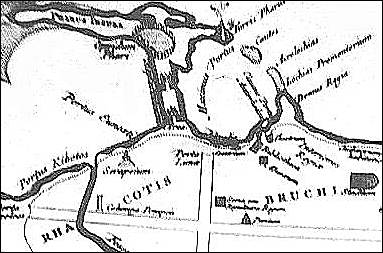

Can we locate the Soma on a map of Ancient Alexandria? Some archaeologists suggest its location at the intersection of the Horreya (Canopic) and Nabi Daniel streets - ancient streets L1 and R5, according to el Falaki's plan of the city6. It must be stressed, however, that the topography of Ptolemaic and Roman Alexandria is even nowadays very incompletely known. The modern town built in the early 19th century by Mohammed Ali coincides with the antique city, which lies beneath it. Until 1865, when Mahmoud Bey el Falaki7 was ordered by the Khedive Ismail to draw a plan of the ancient city (to comply with a request of Napoleon III), no topography was known of the city of the Ptolemies8 and no reliable archaeological excavation had ever been carried out. The map was completed in 1866, and it also showed the remains of the massive city fortifications. These walls finally disappeared completely with the urbanization work that started after 1882.

Later, sporadic excavations by Neroutsos, Botti, Hogarth, Noack, Breccia and others revealed sections of the ancient streets and remains of buildings, but no methodical excavations were carried out in the centre of the town. These had to wait until 1960, when the Polish excavations began 9. These excavations were concentrated in and around the mound of Kom el Dick. They unearthed the Greek and Roman residential quarter at the ancient street R4, and public quarter further to the East with Roman theatre, so called Theatre street, row of public auditoria, imperial bath, aqueduct, large cistern (castellon), two Arab necropolis on the upper levels (7th-13th century), early Islamic houses, workshops etc 10. However, the modern plans on the topography of Ancient Alexandria still greatly rely on the Falaki plan.

Mahmoud el Falaki located the tomb of Alexander the Great in the center of the city, at the intersection of the Via Canopica (Horreya Av.) and the ancient street R5, not far from the Mosque of Nabi Daniel. Since then the tomb of Alexander the Great has been located on the same place by some other scholars such as Neroutsos, Kiepert and Sieglin. However, the modern excavations conducted around the Mosque and its vicinity excluded the possibility of existence of the Ptolemaic Necropolis in this area 11.

Adriani suggested the location of the Soma in the north-eastern part of the ancient city, which lies much closer to the Royal Quarter.

The remains of an ancient thumulus tomb made of alabaster, situated at the present Latin Cemetery, is at least a relative of Macedonian chamber tombs, and marks the area of Ptolemaic Cemetery of the most upper class, or even royal12.

Photos: (top) Illustration of the funeral cart; (middle) 18th century illustration of the funeral cart of Alexander; (bottom) the catafalque which bore the body of the conqueror to the city he had founded - imagined by Carl Otfried Muller.

Notes:- 3. Diodorus Siculus, XVIII, 26, 27, 28.

- 4. Le Compte de Caylus. Sur le char qui porta le corps d'Alexandre. Histoire de l'Academie Royale. (1978).

- 5. ÓÞìá according to Strabo, Zenobius, Sozomenou, Óþìá according to the Pseudo Callisthenes.

- 6. Based on Strabo's description that the Soma was part of "The Palaces", Fraser suggests that it may lay near the coast in the Eastern part of the city P.M. Fraser.

- 7. Mahmoud el Falaki, Mémoire sur l'anciénne Alexandrie, Copenhaguen, (1872).

- 8. Except for the study undertaken by the French scientists of Bonaparte's expedition. Gratien Le Père, "Mémoire sur la ville d'Alex." Déscription de l'Egypte, t. 18, pp. 183-490.

- 9. K. Michalowski, " Rapport sur la prospection du terrain dans la région de Nabi Danial", Bull de la Faculté des lettres de l'Université d'Alexandrie, XII, (1958), pp. 37-39. L. Dabrowski, Polish Research on Ancient Alexandria (in Polish) Meander, 11, (1958), pp. 401-405. L. Dabrowski, "Resumé des recherches archaeologiques faites autour du Fort Kom el-Dikka en Alexandrie". Univ. d'Alex., Bull. Fac. Lettres 14, (1960), pp. 39-49 (with plans). See also J. Lipinska in Etudes et Travaux 3, [Trav. Cent. d'Arch. méd., Warsaw (1966)], pp. 182-199, and W. Kubiak, BSAA 42, (1967), pp. 47-80. M. Rodziewicz, A Brief Record of the Excavations at Kom el-Dikka in Alexandria (1960-1980) in: BSAA 44, Alexandrie 1991, pp. 1-70.

- 10. See: M. Rodziewicz: "Un quartier d'habitation gréco-romain à Kom el Dikka", ET IX, 1976 pp. 169-210: M. Rodziewicz, "Les habitations Romaines tardives d'Alexandrie à la lumière des fouilles polonaises à Kom el-Dikka". (Alexandrie III), Varsovie 1984; M. Rodiewicz, "La stratigraphie de l'antique Alexandrie à la lumière des fouilles de Kom el-Dikka". ET XIV, 1990, p. 146 ff, fig.2.

- 11. For the location of the digging in the area prior the Polish Excavations (1960 present) see: A. Adriani, Reportorio d'Arte dell'Egitto Greco-Romano. Serie C. Palermo (1963) No. 45, fig. E, pl. 22, fig. 77 (plan of the excavation located just beside the eastern wall of Nabi Danial Mosque). For more recent bibliography of the subject see: M. Rodziewicz, Le debat sur la topographie de la ville antique. Alexandrie entre deux mondes, ROMM 46, 4e trimestre (1987), pp. 38-48; M. Rodziewicz, Reports on excavations at Kom el-Dikka: 1960-1980, 1980-1981, 1982, 1983-1984 in BSAA 44, pp. 1-118. In this same volume: Rodziewicz-Ahmed Abdel Fatah, Recent discoveries in the Royal Quarter of Alexandria, BSAA 44, pp. 131-150; Rodziewicz-Daoud Abde Daoud. Investigation of a trench near the Via Canopica in Alexandria, BSAA 44, pp. 151-168. See also M. Rodziewicz, Alexandrie III, op. cit. Varsovie (1984).

- 12. See Adriani, Repertorio, op. cit. p. 242 ff.; N. Bonacasa, Un inedito di Achille Adriani sulla tomba di Alessandro. Studi Miscellanei 28, Roma (1991), p. 3 ff

Let us briefly enumerate the ancient sources that mention the Mausoleum of Alexander.

The fantastic "story of Alexander" was written by an author known to us as Pseudo-Callisthenes at the beginning of the 3rd century AD. It says that the body of Alexander was placed in a lead sarcophagus and was first transported to Memphis and then to Alexandria.

Strabo13 (67-23 BC), says that the Sema is part of Basilea and

included the tombs of the kings and that of Alexander. He mentions that

Ptolemy transported the body of Alexander to Alexandria and gave it burial

in the same location where it lies now, but not in the same coffin….

Strabo13 (67-23 BC), says that the Sema is part of Basilea and

included the tombs of the kings and that of Alexander. He mentions that

Ptolemy transported the body of Alexander to Alexandria and gave it burial

in the same location where it lies now, but not in the same coffin….

"The one in existence now is of glass instead of the one in which originally Ptolemy had deposited the body which was of gold, that coffin was removed by Ptolemy X, Alexander I, son of Kokkis, called Parisactos...", (Reigned from 107 to 88 BC).

Diodorus SiculusM14, who lived at the time of Julius Caesar and Augustus, mentions the "decision not to bury the body in the temple of Amon (at the oasis of Siwah), but in the greatest of the cities of the world, Alexandria. And the body was deposited with great honors, sacrifices and games".

Plutarch, one of the most reliable ancient sources (46A.D. - 127A.D.), who travelled to Alexandria adds: "After the death of Alexander, Python and Seleucus were sent to the Serapeum to ask the oracle if the body should be sent to Alexandria and the god answered that it should be transported there"15.

Zenobius16, a contemporary of Hadrian, mentions that Ptolemy IV Philopator, who reigned from 221-205 BC, decided to group all his ancestors' remains in one mausoleum and in consequence according to this author, the Soma remained empty. Zenobius' description suggests that the Mausoleum built by Philopator and called the Soma was not on the same site as the original tomb of Alexander.

According to Flavius Josephus17, Cleopatra VII Philopator in a moment of financial difficulty looted all the wealth of Alexander's tomb.

Pausanias18, the great traveller of the middle of the 2nd

century (160-180 AD), says that Perdicas' intention was to transport the

body to Aigai, in Macedonia and that Alexander was venerated after his

death as a divinity. According to Pausanias, Ptolemy I Soter (337-283 BC)

deposited the body in Memphis and it was Ptolemy II Philadelpheus (309-247

BC) who transported it to Alexandria.

Pausanias18, the great traveller of the middle of the 2nd

century (160-180 AD), says that Perdicas' intention was to transport the

body to Aigai, in Macedonia and that Alexander was venerated after his

death as a divinity. According to Pausanias, Ptolemy I Soter (337-283 BC)

deposited the body in Memphis and it was Ptolemy II Philadelpheus (309-247

BC) who transported it to Alexandria.

Dion Cassius19, the historian who lived between 155-235 AD and was consul of Africa in the reign of Septimus Severus, reports Augustus' request to see the body of Alexander. "But touching the nose he did some damage to it. Asked if he wanted to visit the tombs of the Ptolemies, he refused, saying that: "I came to see a king and not dead men". He also mentions that Severus placed in the Mausoleum all the secret books "so none could read the books nor see the body".

Lucanus20, the poet (36-65 AD), in his epic poem Pharsalia says that the mausoleum had a pyramidal dome and stood elevated forming a tumulus. This is the only description mentioning a pyramidal superstructure over a vault.

Suetonius21 claims that it was Augustus who refused to see the tombs of the Ptolemies, saying that "I came to see a king and not mortus". He ordered the removal of the body of Alexander from the sarcophagus to honor it, placed a gold diadem and scattered flowers on the tomb.

Another author, Antiochius Grypus, also reports the substitution of the

gold sarcophagus by one made of glass or alabaster by Ptolemy X Alexander

(107-88) because of the cupidity of this kind.

Another author, Antiochius Grypus, also reports the substitution of the

gold sarcophagus by one made of glass or alabaster by Ptolemy X Alexander

(107-88) because of the cupidity of this kind.

Achilles Tatius22, who lived in the 3rd century AD, places the Soma in the centre of the town in a quarter that took the name of Soma from this same monument.

Regretfully, we do not have any reliable ancient artistic representations showing unequivocally Alexander's Mausoleum.

The representation on a Roman lamp in the National Museum of Poznan 23 and others at the British Museum24 and the Museum of l'Ermitage25, are interpreted by some scholars as showing Alexandria. They see a depiction of the main monuments of the royal necropolis with the Soma pictured as a stone building with a pyramidal roof.

Quite recently the proposed identification of the "panorama" of Alexandria depicted on the lams lost its value in the light of the newest investigation done by Bailey, who convincingly proved that the lamps cannot be connected in any way with Alexandria, but with Italy and North Africa26.

However on the sculpted sarcophagus cover of Julius Philosyrius of Ostia26a, we recognise some features fitting to the imagination of ancient Alexandria, built by the literary testimonies, particularly of Strabo text. The Pharos seems to be there, as well as the column Diocletian. A round tower, with a conical roof, is identified with the Soma. If this interpretation is correct, we have a testimony that the Soma and the monuments in its immediate vicinity survived after Diocletian's sack of the town. The column was erected in 296 after the rebellion of the Alexandrians27.

Herodian28 reports in detail the visit of Caracalla to the Soma, as does a later historian of the Christian era, John of Antiochia. In his history from Adam to 518 AD, the latter says that when Caracalla, entered the Tomb of Alexander, he removed his tunic, his ring, his belt and all other precious ornaments and deposited them on the coffin.

It should be noted that in 215 Caracalla sacked the town of Alexandria but apparently respected the Mausoleum of Alexander. Unfortunately for Alexandria, the sack of Caracalla was neither the first nor the last of its vicissitudes.

Photos: (top) Engraving of Julius Caesar paying homage to the body of Alexander; (middle) Silver coin with bust of Cleopatra VII circa 40BC; (bottom) Marble head of Alexander the Great.

Notes:- 13. Strabo, Geogr. XVII, C. 793, 794.

- 14. Diodorus Siculus, XVII.

- 15. Plutarch, Alex. 76.

- 16. Zenobius, III, 94; cf. Pausanias 1,7.

- 17. Flavius Josephus, Contra Apion., II, 57.

- 18. Pausanias, 1,6,3.

- 19. Don Cassius, LI, 16 and LXXV, 13.

- 20. Lucanos, Pharsalia, VIII, 694: X, 19.

- 21. Suetonius, vit. Auq. XVIII.

- 22. Achilles Tatius, V, I.

- 23. M.L. Bernhard, Topographie d'Alexandrie: le tombeau d'Alexandre et le mausolé d'Auguste, Rev. Archéol. (1956) I, pp. 129-156, and Lampki starozytne, arsaw, (1955), p. 137.

- 24. M.B. Walters, Cat. Of the Greek and Rom. Lamps in the British Museum, (1941). [= Guide Greek and Roman life, (1920), fig. 28, p. 38].

- 25. O. Waldhauer, Die antiken Tonlampen, Kaiserliche Ermitage, St. Petersburg, (1914).

- 26. See D.M. Bailey, Alexandria, Carthage and Ostia. Alessandria e il mondo ellenistico-romano. Studi in onore di Achille Adriani, 2. Roma1984, pp. 265-272, pl. XLVII. (Lamps later dating to early 3rd cent. A.D.) Group 7 - false examples. Foreigners made in Naples, Bailey op. cit. p. 269.

- 26a. Ch. Picard, BCH, 76, 1952, p. 92, fig. 14.

- 27. One of the numerous panels of opus sectile (IV c.A.D.) found at Kenchreai probably depicts an Alexandrian port. But is this a port on lake Mareotis or a sea port? The scene is worth been studied and its buildings interpreted. See Leila Ibrahim, Kenchreai, Eastern Port of Corinth, Vol. II, Leiden (1976).

- 28. Herodian, IV, 8, 9, cf. P. Benoit and J. Schwartz Etud. pap. 7, (1948), 17-23.

In the 3rd century under Claudius II (269), Aurelian (273) and Diocletian (296) terrible repression against the population of Alexandria destroyed nearly the whole of the city29. Natural disasters contributed also to the devastation of the ancient city. The earthquakes of the 4th century possibly changed some areas beyond recognition. Fallen buildings were not reconstructed then, but their elements were reemployed in other private and public edifices. Then the ruined eastern area of the Ptolemaic city was left extra muros, and the Ptolemaic Royal Quarter was deserted. Most probably the Royal cemetery followed the fate of the palaces and the precise location of the tomb of Alexander the Great has been forgotten.

We do not have historical evidence on any particular action against the tomb of Alexander the Great in late antiquity. However some historical sources depict remarkable destructive tendencies in Alexandrian society, when under the emperor Theodosius (379-395), Christianity became the state religion.

After the end of the 4th century, we do not have any reliable witness claiming to have seen the Soma, and it is understandable why St. John Chrysostom30 the Bishop of Constantinople (344 or 347-407) asks in his homily, wanting to emphasize the futility of this world: "Tell me where the Sema of Alexander is"?

By asking that question, the prelate was making an example of one of the most famous buildings known by his people to have certainly existed, but which all were aware had totally disappeared. He knew quite well that no one could reply: "I know where the Sema is". But Chrysostom also warned against the talismanic habit of adorning necks and ankles with necklaces made of coins bearing the head of Alexander with the ram horns. This is a further indication that his cult was deeply rooted even in the second half of the 4th century AD.

There is also a further mention of the Tomb of Alexander at the decline of the Ancient world, which is included in the Synaxari of Alexandria 31. It says that at the time of the Patriarch Theophilus (385-412) while digging the foundations of the church of the prophets Elias and John a slab of marble with three "Q's" was found. It was said that this slab covered a treasure of the time of Alexander. The church was called Dimos or Demos and was built on an elevation. It is probable that this location was chosen on purpose in order to sanctify pagan ground by the veneration of the relics of two prophets. But there are also written testimonies for the existence of an early Christian church erected in this vicinity called the church of Alexander32.

Procopius33 , (end of the 6th c.-562) says that until the reign of Justinian, sacrifices were made in honour of Ammon and Alexander the Macedon. A representation of Alexandria has survived to our day in a mosaic of the 6th century, at Jerash. It bears the inscription ALEXANDREIA in Greek and represents the city surrounded by tall walls34. A building with a tholos roof is interpreted by some scholars as the Soma, while in the neighbouring building they see the temple assigned to the cult of Alexander. Another important building with a cupola may well be the old church of St. Mark.

The question that arises is: how can we accept the existence of the Mausoleum of Alexander nearly two centuries after the presumable date of its disappearance? This can be explained if we say that the artist was copying an early prototype, or if he was depicting an idealized view showing the most famous buildings that had been known to exist in the great town. This can lead to the supposition of the existence of a prototype of the 1st century AD or earlier, which might have been the common source of inspiration for the lamps, the sarcophagus and the mosaic.

Notes:- 29. Mommsen, Rom. Gesch., V, 570.

- 30. Ed. Montfaucan, X. 625. Σώζομεν. Ιστορ. εκλ 7.25. Ίωάν. Χρυσοστ. Επιστολή προς Κορινθίους ομιλία 26 κ. 12 "Που γάρ, είπε μοι, σήμα Αλεξάνδρου, δειξόν μοι,.."

- 31. Synaxari of Alex., P.O.I., pp. 131-133, 345-317 Bibl. Nat. de Paris, Mss. Arabes 203, to 283a.

- 32. There is a tradition among the monks of the Monastery of St. Makarios in the oasis of Wadi Natrun, that some bones alleged to be the remains of St. John the Baptist and other martyrs were transported in the 7th century from this church and deposited in the Monastery's ossuary. This eventually coincides with the destruction of the church of Alexander by the Arabs and explains the attempt made by Christians to safeguard what were believed to be holy relics, in a far remote monastery of the Libyan desert.

- 33. Προκοπ. περί κτισμ. σ. 2

- 34. Ch. Picard, BCH, 76, (1952), I, p. 76; fig. 7 and 8.

In the year 641-2 Alexandria was taken by the Arab general Amr. It must be accepted that notwithstanding the repeated destruction, Alexandria was still a sizable city, as Amr in his report to the Caliph mentions that the town had: 4,000 palaces, 4,000 baths, 400 arenas and theaters and 1,200 gardens. Although these figures are exaggerations, what remained of ancient Alexandria obviously impressed the general.

The Arabs referred to Alexander as Eskander or Dzoul Karnein, the "Sire

with the double horns" because of his portrait with ram horns on the

Ptolemaic coins. The horns symbolized strength but also spiritual power.

Often he was also called a Nabi; a Prophet: Nabi Eskender. And Alexandria

was named and is still called Eskandereya.

The Arabs referred to Alexander as Eskander or Dzoul Karnein, the "Sire

with the double horns" because of his portrait with ram horns on the

Ptolemaic coins. The horns symbolized strength but also spiritual power.

Often he was also called a Nabi; a Prophet: Nabi Eskender. And Alexandria

was named and is still called Eskandereya.

Although one should be sceptical as to whether the Great Library of Alexandria was destroyed by Amr and of the manner in which it is described, it can be said with certainty that the destruction of what had been spared until then of the Great City followed the Arab conquest. The town totally lost its importance and the destruction was completed by the Turks at the beginning of the 15th century.

But Alexander and his tomb are remembered in the Arab tradition and are referred to by Macoudi35, who mentions a modest construction existing in Alexandria until 943-944 called the "Tomb of the Prophet and king Eskender".

Then it seems that we have a gap and we hear no more about Alexander's tomb for five centuries.

The destruction of Alexander's Mausoleum must not surprise us, as besides repeated disasters due to man, tremendous earthquakes, sometime with tidal waves, caused the subsidence of the geological plateau, which led to the poor state of preservation of all the ancient and early medieval town 36. Another famous and enormous Alexandrian building, the Pharos has completely disappeared37. But while for the Pharos the location is known with certitude and some of its architectural remains can still be seen, the Soma seems to have totally vanished.

In the early part of the 16th century, Leo the African38 (1494-1552) sought for the vestiges of Alexander's tomb and was shown a small building venerated by the Mohammedans who deposited in it offerings.

The traveller Marmol39 in 1546 was also shown a small building venerated by the Arabs as the tomb of the Prophet Eskender in the center of the town among the ruins. Similar mention is made by the travellers Geo Sandys40 and Michael Radzivill Sierotka41, at the end of the XVI c. (1582-1584). J.J. Ampère says that the Arabs of Alexandria showed in the XV c. the tomb of the prophet Iskander 42.

At that time the once great city, numbered probably only 6,000 43 inhabitants. The natives had withdrawn from the Greco-Roman town to the site of the Heptastadion that connected the mainland to the island of Pharos and had been reclaimed over the centuries by the Nile's alluvium.

Photos: (top) Silver coin of Alexander wearing the horn of Ammon. Issued by his successor Lysimachus in 280BC and probably based on the idealised portraits in his lifetime by court gem-artist, Protogenes; (bottom) The Pharos.

Notes:- 35. Macoudi: Les prairies d'or, transl. By O. Barbier de Meynard and Pavet de Courteille, t. II, p. 259.

- 36. Mieczyslaw Rodziewicz, "Graeco-Islamic Elements of Kom el Dikka in the light of the new discoveries; Remarks on early Mediaeval Alexandria, Graeco-Arabica, Vol. I, Athens (1982).

- 37. The Pharos had been partly preserved up to the medieval times as it was restored then transformed into a mosque, but was totally destroyed in 1303 during the tremendous earthquake.

- 38. Descrizione dell'Africa (for this work see R. Brown's exhaustive ed.of J. Powys's translation (1600), Description of Africa, 3 vols. (Hakluyt Soc., no 92-4, London, 1896).

- 39. Marmol, De l'Egypte III, p. 276, lib. XI, cap. 14.

- 40. Geo Sandys, Relation of a journey, cf. H. Tierch, "Die Alex. Konigsnecropole", JDI, XXV, (1910), pp. 53-92.

- 41. Hierosolymitana peregrinatio illustrissimi domini Nicolai Christopheri Radzivilli, … Ex idiomate Polonica in latinum linguam translate... Thorma trelere interprete, Brunsbergae, (1601) and Polish, Krakow, (1925), p.120.

- 42. J.J. Ampère Voyage en Egypte. Rev. des deux Mondes. (1846).

- 43. According to M.F. Awad the estimated population of Alexandria in 1806 was 6,000 inhabitants, in 1821 12,000 inhabitants, in 1835 52,000, in 1868 200,000; the census of 1897 listed 316,699 souls, of 1917 458,539, of 1947 949,446, rising to 1,516,234 in 1960 ROMM 46, (1987) 4.

In the year 1731, the French traveller Bonamy visited Alexandria and made drawings of what he considered had been the Soma and other ancient ruins. He also drew a map of the ancient city and tried to identify the ruins with ancient sources. His plan however is very sketchy and locations of existing then monuments such as "Pompey's Pillar" and Serapeum are put evidently on the wrong side of the Via Canopica. Unfortunately the Soma and Paneum is noted on his plan erroneously on the northern side of the Canopic street. Therefore it is not certain whether Bonamy associated the Soma and Paneum with the hill Kom el Dick and Nabi Daniel Mosque, which were located south of the Via Canopica. All other plans of the city depict Kom el Dick hill and Serapeum on the southern side of the Canopic street. Therefore Bonamy contributed only to the existing confusion, and produced a pictorial equivalent of misty legend, possibly drawn from memory.

Certainly the natives, living outside the city walls, in their small village, on the land formed by the alluvium of the Nile on the ancient Heptastadion, could not discern among the ruins of the ancient buildings the remains of the Soma, for the very reason that in fact no remains were left. Failing that they "invented" a supposed location - actually more than one - where they could give free access to their devotion to the founder of the town.

What also, probably stimulated their zeal to find a substitute for the Mausoleum was the fact that European travellers were increasingly visiting the ruins of the ancient city. Armed with translations of the ancient authors they asked to be shown the remains of the famous ancient buildings and of the tomb of Alexander.

For the shrewd local dragomans it was lucrative to guide those early "tourists" around the ruins and certainly rewarding to answer positively to the question: Can you show me King Eskender's tomb?

Two buildings won the preference of the natives and were shown as Alexander's tomb. Their choice was not picked out at random but dictated by local tradition, which generation after generation had preserved faint memories of the Soma. The building shown in earlier times was the old church of St. Athanasius, transformed after the Arab conquest into the mosque of Attarine44.

In the inner court of this mosque, one could see an impressive pharaonic

sarcophagus of granite covered with hieroglyphs. We now know, after the

decipherment of the hieroglyphs, that it originally contained the body of

Pharaoh Nectanebo II (Nekthar-heb), the very last Pharaoh. But so

persuasive was the way the natives presented it as Alexander's tomb, that

at the beginning of the 19th century a dispute arose between the French

and the English about its possession.

In the inner court of this mosque, one could see an impressive pharaonic

sarcophagus of granite covered with hieroglyphs. We now know, after the

decipherment of the hieroglyphs, that it originally contained the body of

Pharaoh Nectanebo II (Nekthar-heb), the very last Pharaoh. But so

persuasive was the way the natives presented it as Alexander's tomb, that

at the beginning of the 19th century a dispute arose between the French

and the English about its possession.

Finally in 1803 the so-called sarcophagus of Alexander made its way to the British Museum. It is said that the inhabitants of Alexandria deeply resented the expatriation of this relic, which they had worshipped as the tomb of the Prophet Eskender for centuries. This sarcophagus was described in detail by Dr. Edward Daniel Clarke45 who believed that the courtyard of St. Athanasius' mosque with the numerous ancient columns was in fact the Soma.

It is worth noting at this point that the Pseudo-Callisthenes says that Alexander was not the son of Philip but that his father was Nectanebo, an Egyptian magician who exercised his art at the Macedonian court. The parallel with the last Egyptian Pharaoh is obvious.

But how can we explain the transportation of this sarcophagus from Sais to

Alexandria and its presence in the Paleochristian church of St.

Athanasius? It is believed that this sarcophagus, like other similar ones,

had earlier been used by the Ptolemies and later by the Christian bishops

for their own burial. It was a readily available monument of fine quality

in the declining Alexandria.

But how can we explain the transportation of this sarcophagus from Sais to

Alexandria and its presence in the Paleochristian church of St.

Athanasius? It is believed that this sarcophagus, like other similar ones,

had earlier been used by the Ptolemies and later by the Christian bishops

for their own burial. It was a readily available monument of fine quality

in the declining Alexandria.

In view of gathered information mentioned above, we have to dismiss the possibility that this sarcophagus contained the body of Alexander.

Photos: (top) Detail of the map drawn by Bonamy in 1731; (middle) The inner courtyard of the Mosque of St. Athanasius (Mosque Attarine) as drawn by D. Clarke. The small building in the centre with the cupola contained the sarcophagus attributed to Alexander; (bottom) The sarcophagus of Pharoah Nectanebo as drawn by D. Clarke.

Notes:- 44. The Mosque of Attarine as we know it nowadays was built later in the middle of the XIXth c. on the same location.

- 45. D. Clarke, The Tomb of Alexander, a dissertation on the sarcophagus from Alex. and now in the British Museum, Cambridge (1805).

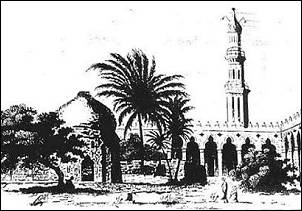

The other location alleged to be Alexander's tomb was the site of the mosque of Nabi Danial. These two mosques Nabi Danial and Athanasius are not far away from each other, and some confusion during the dark ages of Alexandria can be justified.

The present Mosque of Nabi Danial was built at the end of the 18th 46 century and restored in 1823 by Mohammed Ali. A smaller shrine, probably the mosque of Dzoul Karnein - the Sire with the two horns - preexisted on the site47. The location is very close to the intersection of the ancient Via Canopica and the street R5. In its crypt there is a catafalque, made in the Moslem tradition. It is said to contain the remains of the scholar and venerated teacher Prophet Daniel and his companion Sidi Lokman el Hakim, a religious story-teller.

The Arab legend of the Prophet Daniel appeared during the 9th century and

was told by two astronomers: Mohamed Ibn Kathir el Farghani and Abou

Ma'shar48 . The story is interesting because it differs greatly

from the Bible and has similarities with Alexander's story. It is

mentioned that "a young Jew, Daniel, was persecuted and chased from Syria

by the idolaters whom he had tried to convert. An old man appeared in a

dream urging him to go to war against the infidels and promising victory

over all of Asia. Daniel acquired numerous followers in Egypt, where he

had sought refuge, and built Alexandria. Obeying what the old man had

ordered him in his dream, he made war against the infidels. After a

successful expedition, he returned to Alexandria and died of old age. His

body was placed in a golden sarcophagus inlaid with precious stones, but

the Jews stole it to mint coins and replaced it with a stone sarcophagus".

The Arab legend of the Prophet Daniel appeared during the 9th century and

was told by two astronomers: Mohamed Ibn Kathir el Farghani and Abou

Ma'shar48 . The story is interesting because it differs greatly

from the Bible and has similarities with Alexander's story. It is

mentioned that "a young Jew, Daniel, was persecuted and chased from Syria

by the idolaters whom he had tried to convert. An old man appeared in a

dream urging him to go to war against the infidels and promising victory

over all of Asia. Daniel acquired numerous followers in Egypt, where he

had sought refuge, and built Alexandria. Obeying what the old man had

ordered him in his dream, he made war against the infidels. After a

successful expedition, he returned to Alexandria and died of old age. His

body was placed in a golden sarcophagus inlaid with precious stones, but

the Jews stole it to mint coins and replaced it with a stone sarcophagus".

A Russian monk, Vassili Grigorovich Barskij49 , visited Alexandria in 1727 and 1730 and made a plan of the city. Near the Kom el Dick mound he drew a small Mohammedan shrine, among ruins, that could well be the predecessor of the Nabi Danial Mosque. I cannot refer to his written description of the city, as Barskij's work is only partially translated and only fragments have been studied.

The Danish Captain Norden visited the town in 1737, but tried in vain to find the tomb of Alexander50.

Similarly, James Bruce 30 years later in 1768 looked for the tomb of the Great Macedonian, "asking the Arabs, the Jews, the Greeks51 and others, but none were able to show him the location".

However, at the end of the 18th century, Sestrini was shown the sarcophagus in the Attarine mosque as having been Alexander's tomb.

In 1803, a Russian prelate from Kiev, the archimandrite Konstantios

52, tried without success to locate Alexander's Mausoleum,

noting that he… "looked in vain for… the tomb of Alexander the Great, the

tomb of the man whose life's course was above the faith of common

mortals...;" he continues, saying that "until the 15th century the

location was known but now even the tradition of this tomb has been

lost...", adding that "beyond any doubt the remains survived under the

great masses of the city's ruins".

In 1803, a Russian prelate from Kiev, the archimandrite Konstantios

52, tried without success to locate Alexander's Mausoleum,

noting that he… "looked in vain for… the tomb of Alexander the Great, the

tomb of the man whose life's course was above the faith of common

mortals...;" he continues, saying that "until the 15th century the

location was known but now even the tradition of this tomb has been

lost...", adding that "beyond any doubt the remains survived under the

great masses of the city's ruins".

It is interesting to note that, strangely enough Konstantios, in his writing, and Barskij53 in his plan do not mention either of the Mosques. Were they have shown one of the Mosques as being the location of Alexander's tomb, and was it because of bigotry or because of their superior knowledge of history that they do not even mention these humble Mohammedan shrines as possible remains of the famous Mausoleum?

A new impulse was given to the legend of the tomb of Alexander the Great in the middle of the 19th century. In 185054 a certain Scilitzis of the known Greek family in Alexandria, dragoman-interpreter to the Russian consulate of the town, produced a fantastic story.

It happened that, while guiding some European travellers entrusted to his care, he entered the crypt of the Nabi Danial Mosque. He "descended into a narrow and dark subterranean passage and came to a wooden worm-eaten door. Looking through the cracks of the planks he saw a body with the head slightly raised lying in a crystal coffin. On the head, there was a golden diadem. Around were scattered papyri, scrolls and books. He tried to remain longer in the vault but he was pulled away by one of the monks of the Mosque, and notwithstanding his repeated attempts to return, he was forbidden the area of the Crypt. Scilitzis apparently made a written report to the Russian Consul and to the Greek Patriarch of Alexandria 55.

It is obvious that Scilitzis had read Dion Cassius and may have had access to the subterranean passage under the Mosque, but he is not telling the truth. How can we believe that in the humid climate of Alexandria, papyri and books could have survived for over two millenia?

Unlike Ambroise Scilitzis's story, which may be described as an enormous hoax56, we cannot dismiss as such the written report of Mahmoud Bey el Falaki. This learned Egyptian astronomer and engineer visited the crypts under the Nabi Danial Mosque some ten years after Scilitzis while trying to carry our the difficult task of drawing a map of the ancient town as ordered in 1865 by the Khedive Ismail57.

In Mahmoud Bey's report, he says that : "During my visit to the vaults

under that building I entered a large room with an arched roof built on

the ground level of the town. From this paved room inclined corridors

started out in four different directions. Because of their length and

their bad state I could not survey them entirely. The rich quality of the

stones used in the construction and numerous other indications confirmed

my belief that these subterranean passages must have led to the tomb of

Alexander the Great. I therefore, contemplated returning and resuming my

investigations, but unfortunately this was forbidden to me by a superior

order and all the entrance ways were walled up"58.

In Mahmoud Bey's report, he says that : "During my visit to the vaults

under that building I entered a large room with an arched roof built on

the ground level of the town. From this paved room inclined corridors

started out in four different directions. Because of their length and

their bad state I could not survey them entirely. The rich quality of the

stones used in the construction and numerous other indications confirmed

my belief that these subterranean passages must have led to the tomb of

Alexander the Great. I therefore, contemplated returning and resuming my

investigations, but unfortunately this was forbidden to me by a superior

order and all the entrance ways were walled up"58.

El Falaki was not an archaeologist, so we can be skeptical about his conclusions, but I would not question his sincerity and he must be considered as a reliable witness.

His description raises some questions: Who decided and why, to force El Falaki to suspend his survey of the subterranean passages? Falaki was working for a project sponsored by the reigning Khedive. Why did he not appeal to his powerful patron? Why did he drop his investigation?

But, before the end of the 19th century, we have a story that must be taken with reservation. It concerns the alleged discovery made in 1879 by a chief mason and the Cheih of the Nabi Danial Mosque. The story goes that while doing some masonry work in the basement they supposedly entered the vault and reached an inclined subterranean passage. They both walked for some distance and could discern some monuments made of granite ending with an angular summit. The mason wanted to proceed further but the Cheih ordered him to return. The entrance was walled up and the mason was asked not to reveal that incident59.

The specific connection of Alexander with the site of Nabi Danial mosque is attested at least from the earlier part of the 19th century by Yacub Artin Pacha, who wrote to Zogheb60.

Photos: (top) The Mosque of Nabi Danial - photograph from the beginning of the 20th century; (middle) head of Alexander; (bottom) Engraving of the Alexandrian Catacombs.

Notes:- 46. According to Fraser the foundation of this mosque may go back to the XVth c. P.M. Fraser op. cit., p. 38.

- 47. Cited by Ibn Abd-el-Hakim, who died in 871 A.D. in his account of the mosques of Alexandria. This author stipulates that "the mosque of Dzoul-Karnein was situated near the gate of the city and its exit. [p. 484 transl. Bouriant Mιm. Miss. Arch. Franη. XVII. I (1893)].

- 48. A. Bernard, "Alexandrie la Grande", Rev. Arch., (1956,5).E.Combe, cited by E. Breccia, "Le tombeau d'Alex. le Grand", in Le Musιe Grec-Rom. 1925-1931 (1932), pp. 37-48 and pl. XXVII-XXXI.

- 49. Grigorovich Barskij. Η περιήγηση του Βασιλείου Γ.Β. στους Άγιους Τόπους της Ανατολής από το 1723 ως το 1747,εκδιδομένη από την Ορθόδοξη Παλαιστινιακή Εταιρεία, με επιμέλεια του N. Barzoukov. Πετρούπολη (1885-1887).

- 50. F.L. Norden, Travels in Egypt and Nubia, translated from the original, p. 33. London (1757).

- 51. M.F. Awad [ROMM 46, (1987) 4] mentions that in the census of 1801, there were 40 Greek families in Alexandria. It should be noted that after the Arab conquest, there is no reference to the Greek community giving information about Alex.'s tomb. The reports are always Arabs.

- 52. Αρχαία Αλεξάνδρεια - Περιγραφή του Κιαίβου - Αικατερινο-Γραικού Μοναστητίου - Αρχιμανδρίτου Κωνσταντίου. Μόσκοβα (1803). 53. Barskij plan contains several annotations of the monuments and locations considered of importance.

- 54. A. Max de Zogheb, Etudes sur l'Anc. Alex., (1909).

- 55. Th. Moshonas of the Patriarchate of Alexandria looked for this document in the Patriarchate's archives but could not trace it. Β. Μοσχονάς, "Ο Τάφος του Μ. Αλεξάνδρου", Κρίκος, London, (Ιούνιος1957).

- 56. A Bernard, "Alexandrie la Grande", Rev. Arch. (1956, 1), p. 235.

- 57. It is worth noting that M. Dimitsas in this important work on Alexandria, based on literary sources does not mention Scilitzis story. Ιστορία της Αλεξάνδρειας. Εν Αθήνας (1885).

- 58. A. Max de Zogheb, Etudes sur l'anc. Alex., (1909), p. 160.

- 59. A. Max de Zogheb, Etudes sur l'anc. Alex., (1909), pp. 161-162.

- 60. "Aussi loin que se reporte ma mιmoire, je me souviens de la mosquιe Nebi Daniel, et ce souvenir est indissolublement liι dans mon esprit avec le nom d'Alex.; car il m'a toujours ιtι dit qu'elle contenait le tombeau du Macedonien, et je crois mκme que c'etait en 1850 la croyance gιnιrale ΰ Alex." quoted by Fraser p. 39.

During the second half of the 19th century, when archaeology made its appearance as a discipline, we do have some attempts of excavation aimed at unearthing evidence about the Soma. Schliemann waited for some time in Alexandria hoping to obtain official permission to dig around the mosque of Nabi Danial.

While waiting, he did some digging near the seashore at Ramleh and discovered a Ptolemaic necropolis. Schliemann, however, made it clear that the only place he felt the Soma could be found was in the vicinity of the Nabi Danial Mosque and the digging of Ramleh was undertaken only so as not to remain idle while waiting for the permission, which was never granted 61.

Botti reports that Ioannides discovered in 1893 a cemetery of the last century of the Ptolemies while searching for the Tomb of Alexander 62.

Neroutsos63 writes that in 1874, while digging the foundations of two houses for Kattaoui Bey and a third in front of the mosque of Nabi Danial, parallel to the street, large granite columns were found as well as others of marble fallen nearby and one of these columns is still there, in situ.

Botti mentions that he saw opposite the Kattaoui building, columns lying seven metres under the level of the ground. Botti64 also refers to an early Christian church near Kom el Dick, called the church of Alexander. Adriani however proved that most of the remains can be associated with the ancient colonnade of street R5, whose part has been excavated and exhibited to public. See: A. Adriani, Repertorio, Serie C, op. Cit. No.46, pl. 24, fig. 89.

Hogarth undertook a number of digs near Kom el Dick at the end of the 19th century65.

More excavations were carried out in the first half of the 20th century by Breccia66, Thiersch67, Adriani68, Gaindor 69, Victor Guirguis70 and Wace71. An important work on Alexandria was also written By Alexandre Max de Zogheb 72.

All theses excavations revealed the existence of groups of huge ancient ruins around Kom el Dick hill and not far away from the Nabi Danial mosque.

It must be said that until the middle of our century the Egyptian authorities were reluctant to grant permission for excavations in the vicinity of the mosque of Nabi Danial, not only on religious grounds but also because some of the members of the reigning dynasty were buried nearby.

After the abolition of the monarchy in 1953, the authorities became less sensitive and more open to scientific excavation in the area. Thus, in 1960, we have for the first time a methodical dig by the Polish archaeological expedition, which is still in progress73.

The Polish excavations continued for some 30 years and brought to light burials of the Arab period74, a well preserved small Roman theatre, remains of a late Roman bath, many other constructions and a vast quantity of material from large ancient buildings75.

In the area of the theatre the Polish archaeologists found a small marble head of Alexander, probably datable to the second century AD. Zsolt Kiss, who published this "New Portrait of Alexander", believes that this modest sculpture shows the Macedonian deified hero, with the hair arranged as a Zeus76.

A water cistern under the Nabi Danial mosque was also investigated. However, no evident remains of the Soma were brought to light, although the excavations took place in the immediate vicinity of its supposed location.

The excavations have added much to our knowledge of the topography of ancient and medieval Alexandria without answering the question of the location of Alexander's tomb77. They finally proved that the region around the Kom el Dickhill, situated in the very close neighbourhood of Nabi Danial Mosque, had been used as residential and recreation part of the city from the Ptolemaic, through the Roman, till the early Islamic period. No traces of the Ptolemaic Necropolis - Soma - have been spotted there. See: M. Rodziewicz, "Alexandrie" vol. III, op. Cit.

But the hope of the discovery of the tomb of the Macedonian hero has also lured non-scientists who persist in searching for the splendid Tomb. A typical case is that of a stubborn Alexandrian Greek waiter, Stelios Koumoutsos, who has spent over three decades trying to persuade the Egyptian and the Greek archaeological authorities to let him excavate at a secret location which holds Alexander's remains78.

The other case is more original and concerns an attempt using "psychic archaeology" made in the late 70's in a "search for Alexander the Great's tomb". It is reported that with the assistance of an Egyptian archaeologist a hole was opened from inside the crypt of the Nabi Danial mosque through a brick wall in an attempt to confirm a "psychic vision" claiming the existence of a subterranean tunnel. However as in three previous cases - Scilitzis', Falaki's and the mason's - at the last moment the investigation was stopped and orders were given to close up the opening79.

But the mystery of the tomb of Alexander the Great, far from having been elucidated, remains80. It is a vivid example of a deeply rooted veneration of a deified hero of the Greco-Roman world that survived Christianity and found, later, a continuity in the Arab tradition.

HARRY E. TZALAS

ABBREVIATIONS USED

BCH = Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique

BSAA = Bulletin Societé Archéologique d'Alexandrie

ET = Etudes et Travaux (Trav. Cent. d'Arch. méd.), Varsovie

Fraser = P.M. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria, Vol. I, Oxford (1972)

JDI = Jahrbuch des Kšnig. Deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts

ROMM = La Revue de l'Occident Musulman et de la Méditerranée.

- 61. This is reported in a monograph written by a Prince Tewfik, The Tomb of Alex. the Great, which I read in the library of the Greco-Roman Museum of Alex. in 1954, but I was unable to trace again in 1988.

- 62. G. Botti, Plan de la ville d'Alex. à l'époque Ptolemaique. Soc. Arch. d'Alex. (1898) Alexandria.

- 63. T.D. Neroutsos, l'Ancienne Alex. (1888).

- 64. G. Botti, Plan de la ville d'Alex. a l'époque Ptolemaique, Alexandria (1898), and Additions au "Plan de la Ville d'Alex. etc.", Bull. Soc. Arch.d'Alex. Alexandria (1898), fasc. 1, p.55.

- 65. D.G. Hogarth and E.F. Benson, Research in Alex. Egypt expl. Fund, Arch.Rep. 1894/1895, p. 13.

- 66. E. Breccia, "La tomba di Aless. Magno", Bull. Arch. N.S., 7 (1929-1930), p.206-208, "Alexandrea ad Aegyptum", pp. 83-86, Berg (1914) and "Sondages près de la Mosquée Nabi Daniel et dans la rue el Bardissy", Le Musée Grec.-Rom. (1925-1931), pp. 48-52.

- 67. H. Thiersch, "Die Alexandrinische Konigsnecropole", JDI, XXV, (1910), pp. 55-97.

- 68. A. Adriani, "Saggio di una pianta arch. di Aless.", Ann. Du Musée Greco-Romain, fasc. I (1932-1933); id. Fasc. III (1935-1939); id. "Scavi e scoperte Alessandrine, (1949-1952)", Bull. Soc. Arch. d'Alex. Alexandria (1956), fasc. 41, pp. 1-10.

- 69. P. Gaindo, "Alexandrie, Recherche du tombeau d'Alexandre", Chron. Egypt. X. (1935), pp. 276-281.

- 70. Unpublished reports on the excavations in the possession of the library of the Grec.-Rom. Museum in Alex.

- 71. A. J. Wace, Unpublished reports dated 1952, in possession of the faculty of Arts Univ. of Alex.

- 72. A.M. de Zogheb, recherche sur l'Ancienne Alex. Pp. 151-174.

- 73. See : M. Rodziewicz, "Alexandrie" I, III op. cit.;BSAA 44,Alex. 1991,pp. 1-168;id. Twenty years of Activities of the Polish Excavation Mission in Alexandria. Africana Bulletin Nr. 31. Warsaw (1982), pp. 11-18

- 74. See : M. Rodziewicz, "Alexandrie" I, III op. cit. See also reports on excavations at Kom el Dikka in Études et Travaux, Varsovie vol. I-XIV; id. Twenty years of Activities of the Polish Excavation Mission in Alexandria. Africana Bulletin Nr. 31. Warsaw (1982), pp. 11-18. TL. Dabrowski, "Two Arab Necropoles Discovered at Kom el Dikka, Alexandria". Trav. Du Centre d'Archaéologie Mèd. de l'Acad. Polonaise de Science . III, pp. 171-180.

- 75. The fort Kom el Dick was built by Marmont as the main fortress of Alexandria.The name Kom el Dick or Kom el Dikka apears in the literature for the first time in 763A.H. (1361 A.D.), when mentioned by the Egyptian writer Al Nuwayri. See Et. Combe, "Note de Topographie et d'Hist. D'Alex.", Bull. Soc. Arch. d'Alex. Alexandria (1946), fasc.36, (1943-1944), pp.142-143.

- 76. Zsolt Kiss, "Un Nouveau Portrait d'Alex. Le Grand". Etudes et travaux Tome 10,IV, pp. 119-131.

- 77. Zsolt Kiss, "Un Nouveau Portrait d'Alex. Le Grand". Etudes et travaux Tome 10,IV, p. 120. "Depuis bien longtemps on situait dans ces parages [Mosquée Nabi Daniel] le fameux Sema, le fastueux tombeau…d'Alex. le Grand. Tous les efforts dans le but de retrouver cet édifice n'ont jusque'hui rien donné". See remarks on Soma in Rodziewicz, "Alexandrie" vol. III, chapter I-IV, op. cit.

- 78. A file with his theories and all pertinent documantation was deposited in 1979 with the Greek Minister of Culture. A. Bernard refers to this same person in p. 236 of his important work, Alexandrie la Grande. Stelios Koumoutsos continued his attempts until 1991, the year he died. He did apparently obtain permission , and dug sporadically in an unscientific manner, at several locations of the city, but lacking the basic topographical knowledge of ancient Alexandria he was led to believe that he was on the right path whenever he did reach the remains of the extended ancient sewage system. Panaigyptia, N. 41, Athens (September 1991).

- 79. Stephan A. Schwartz, The Alexandrian project, New York (1983).

- 80. During Februaury and October of 1992, the Greek press and several foreign papers reported an announcement made by an archaeologist, Mrs. Liana Souvaltzi, stating that during an excavation at Siwa a building believed to be the tomb of Alexander was found. No conclusive evidence was given so it only adds a further, most improbable version to the legend of the lost tomb.

Note by the author : I am greatly indebted to Prof. M. Rodziewicz who kindly read this text and made valued comments.