The role of Alexandria in the Mediterranean

Scholars and Scholarly Thought

The magnitude of the project could be gauged by the fact that the building, which was started about 290 B.C., lasted some ten years before it was finally completed under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The light projected from its uppermost part reached over 300 stadia or about 50 metres into the sea - a sure outcome of putting to use the scientific specialisation which had started earlier at the Lyceum of Athens and was later to reach its climax in the research halls of the Mouseon of Alexandria.

The magnitude of the project could be gauged by the fact that the building, which was started about 290 B.C., lasted some ten years before it was finally completed under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The light projected from its uppermost part reached over 300 stadia or about 50 metres into the sea - a sure outcome of putting to use the scientific specialisation which had started earlier at the Lyceum of Athens and was later to reach its climax in the research halls of the Mouseon of Alexandria.

That the lighthouse, or the Pharos - as it was called after the name of the former island where it finally stood - greatly helped in enhancing trade activity in the Mediterranean , must have been abundantly clear to the classical authors. Centuries after its completion, they could still express, in more ways than one, their fascination both by the building and its components and by the services it rendered to trade.

That the lighthouse, or the Pharos - as it was called after the name of the former island where it finally stood - greatly helped in enhancing trade activity in the Mediterranean , must have been abundantly clear to the classical authors. Centuries after its completion, they could still express, in more ways than one, their fascination both by the building and its components and by the services it rendered to trade.

Sometime after his stay in Alexandria in c.25-4 B.C., Strabo talks in his Geography (XVII, 11) of its lighthouse and the singular service it offered to the ships during their nocturnal approach to the eastern harbour or the 'Great harbour' of Alexandria. Although Plinius the elder, contrary to his habit of lengthy descriptions talks only briefly about the Alexandrian Pharos in his "Historia Naturalis" (XXXVI, 18) - only understandable in view of Strabo's detailed description more than half a century earlier - he takes particular care to describe it as the prototype of its genre.

Sometime after his stay in Alexandria in c.25-4 B.C., Strabo talks in his Geography (XVII, 11) of its lighthouse and the singular service it offered to the ships during their nocturnal approach to the eastern harbour or the 'Great harbour' of Alexandria. Although Plinius the elder, contrary to his habit of lengthy descriptions talks only briefly about the Alexandrian Pharos in his "Historia Naturalis" (XXXVI, 18) - only understandable in view of Strabo's detailed description more than half a century earlier - he takes particular care to describe it as the prototype of its genre.

Suetonius, writing about A.D. 120, follows suit; when he talks about the lighthouse built in Ostia under the reign of Claudius and the guidance it offers to the ships coming into its harbour at night (De Vita Caesarum, Claudius, 20) he immediately likens it, in this respect, to 'the Pharos of Alexandria' - thus setting the Alexandrian lighthouse as an ideal never to be forgotten.

Suetonius, writing about A.D. 120, follows suit; when he talks about the lighthouse built in Ostia under the reign of Claudius and the guidance it offers to the ships coming into its harbour at night (De Vita Caesarum, Claudius, 20) he immediately likens it, in this respect, to 'the Pharos of Alexandria' - thus setting the Alexandrian lighthouse as an ideal never to be forgotten.

However, the full Mediterranean dimension of the Alexandrian trade had developed long before the classical authors displayed their fascination by the Pharos. A papyrus dating back to the middle of the second century B.C. (Preisigke, Sammelbuch, 7169) presents a contract between a number of businessmen forming an international company with the purpose of conducting commercial transactions. Despite the mutilated condition of the document, the names of seven members of the company could be read, representing six nationalities from the Mediterranean region.

However, the full Mediterranean dimension of the Alexandrian trade had developed long before the classical authors displayed their fascination by the Pharos. A papyrus dating back to the middle of the second century B.C. (Preisigke, Sammelbuch, 7169) presents a contract between a number of businessmen forming an international company with the purpose of conducting commercial transactions. Despite the mutilated condition of the document, the names of seven members of the company could be read, representing six nationalities from the Mediterranean region.

Strabo (XVII,I,13) was obviously referring to the same dimension when he called Alexandria, towards the end of the last century B.C., 'the greatest emporium of the inhabited world'. Over half a century later we learn from the unknown writer of the Periplus Maris Erythraei, a guidebook written for the benefit of merchants and seamen, that Alexandria had become by then, the central post for exchange of overseas trade (Periplus, 26). This would involve, no doubt, the Erythrayean as well as the Mediterranean seas. This is clear from what Josephus tells us (Bell. Iud.,IX,615) when he talks about Alexandria about two decades later, referring to its harbour 'from which the surplus of the local products is distributed to every quarter of the world'.

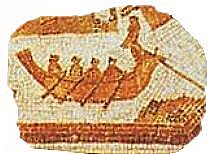

Photos: Sections taken from a mosaic depicting harbour scenes supposed to be Alexandria from the 3rd Century. AD. Tuledo, Spain.