Home

Certainly the natives, living outside the city walls, in their small village, on the land formed by the alluvium of the Nile on the ancient Heptastadion, could not discern among the ruins of the ancient buildings the remains of the Soma, for the very reason that in fact no remains were left. Failing that they "invented" a supposed location - actually more than one - where they could give free access to their devotion to the founder of the town.

What also, probably stimulated their zeal to find a substitute for the Mausoleum was the fact that European travellers were increasingly visiting the ruins of the ancient city. Armed with translations of the ancient authors they asked to be shown the remains of the famous ancient buildings and of the tomb of Alexander.

For the shrewd local dragomans it was lucrative to guide those early "tourists" around the ruins and certainly rewarding to answer positively to the question: Can you show me King Eskender's tomb?

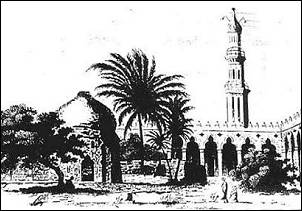

Two buildings won the preference of the natives and were shown as Alexander's tomb. Their choice was not picked out at random but dictated by local tradition, which generation after generation had preserved faint memories of the Soma. The building shown in earlier times was the old church of St. Athanasius, transformed after the Arab conquest into the mosque of Attarine44.

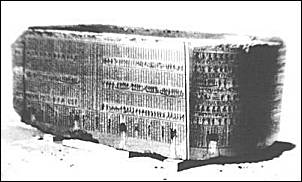

In the inner court of this mosque, one could see an impressive pharaonic sarcophagus of granite covered with hieroglyphs. We now know, after the decipherment of the hieroglyphs, that it originally contained the body of Pharaoh Nectanebo II (Nekthar-heb), the very last Pharaoh. But so persuasive was the way the natives presented it as Alexander's tomb, that at the beginning of the 19th century a dispute arose between the French and the English about its possession.

In the inner court of this mosque, one could see an impressive pharaonic sarcophagus of granite covered with hieroglyphs. We now know, after the decipherment of the hieroglyphs, that it originally contained the body of Pharaoh Nectanebo II (Nekthar-heb), the very last Pharaoh. But so persuasive was the way the natives presented it as Alexander's tomb, that at the beginning of the 19th century a dispute arose between the French and the English about its possession.

Finally in 1803 the so-called sarcophagus of Alexander made its way to the British Museum. It is said that the inhabitants of Alexandria deeply resented the expatriation of this relic, which they had worshipped as the tomb of the Prophet Eskender for centuries. This sarcophagus was described in detail by Dr. Edward Daniel Clarke45 who believed that the courtyard of St. Athanasius' mosque with the numerous ancient columns was in fact the Soma.

It is worth noting at this point that the Pseudo-Callisthenes says that Alexander was not the son of Philip but that his father was Nectanebo, an Egyptian magician who exercised his art at the Macedonian court. The parallel with the last Egyptian Pharaoh is obvious.

But how can we explain the transportation of this sarcophagus from Sais to Alexandria and its presence in the Paleochristian church of St. Athanasius? It is believed that this sarcophagus, like other similar ones, had earlier been used by the Ptolemies and later by the Christian bishops for their own burial. It was a readily available monument of fine quality in the declining Alexandria.

But how can we explain the transportation of this sarcophagus from Sais to Alexandria and its presence in the Paleochristian church of St. Athanasius? It is believed that this sarcophagus, like other similar ones, had earlier been used by the Ptolemies and later by the Christian bishops for their own burial. It was a readily available monument of fine quality in the declining Alexandria.

In view of gathered information mentioned above, we have to dismiss the possibility that this sarcophagus contained the body of Alexander.

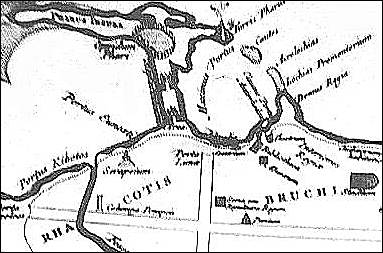

Photos: (top) Detail of the map drawn by Bonamy in 1731; (middle) The inner courtyard of the Mosque of St. Athanasius (Mosque Attarine) as drawn by D. Clarke. The small building in the centre with the cupola contained the sarcophagus attributed to Alexander; (bottom) The sarcophagus of Pharoah Nectanebo as drawn by D. Clarke.

Notes:

44. The Mosque of Attarine as we know it nowadays was built later in the middle of the XIXth c. on the same location.

45. D. Clarke, The Tomb of Alexander, a dissertation on the sarcophagus from Alex. and now in the British Museum, Cambridge (1805).