Library

Alexander the Great -- the Conquests as a source of knowledge

The Founding of the Library and the Mouseion

The Egyptian Section of the Alexandria Library

The Papyri: Evidence of Greek and Egyptian Scientific Interchange

The Pinakes -- a Bibliographical Survey of the Alexandria Library

The Alexandria Library -- " The Memory of Mankind"

Appendix 1 -- The Contents of the Alexandria Library

Appendix 2 -- The End of the Library

References

The Modern

Library

BIBLIOTHECA ALEXANDRINA--The revival of the Ancient Library of Alexandria

Back to Alexandria Home Page

In so far as the Library was required to satisfy the needs of scholars at the Mouseion, this association helped the Library to develop into a proper research centre.

Furthermore, their location within the grounds of the royal palaces, placed them under the direct supervision of the kings (Letter of Aristeas) and this situation was favourably reflected in the rapid growth of the collection of books. Half a century had hardly passed after its foundation in c. 295 BC., when it was felt that the premises of the 'Royal Library' was not large enough to contain all the books that had been acquired, and that it was found necessary to establish an offshoot that could house the surplus volumes.

Furthermore, their location within the grounds of the royal palaces, placed them under the direct supervision of the kings (Letter of Aristeas) and this situation was favourably reflected in the rapid growth of the collection of books. Half a century had hardly passed after its foundation in c. 295 BC., when it was felt that the premises of the 'Royal Library' was not large enough to contain all the books that had been acquired, and that it was found necessary to establish an offshoot that could house the surplus volumes.

This branch library was incorporated into the newly built Serapium by Ptolemy III, Euergetes (246-221 BC.) which was situated at a distance from the royal quarter in the Egyptian district, south of the city.10

As regards the total number of books in the Library various figures were reported at different times:

The earliest surviving figure under the first two Ptolemies is reported as "more than 200,000 books" (Aristeas, 9-10) whereas the medieval text of Tzetzes, derived from an ancient source, mentions "42,000 books in the outer library; in the inner (i.e. Royal Library) 400,000 mixed books, plus 90,000 unmixed books"

A still higher estimate of 700,000 was reported between the second and fourth centuries AD. (Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 7.17.3; Amm. Marcellinus 22.16.13).

An interesting passage in Galen, reveals the existence of an intricate system of registration and classification. The information recorded on each book revealed not only the title of the work and the names of its author and editor of the text, but also the place of its origin, the length of the text (i.e. number of lines) and whether the manuscript was mixed (containing more than one work) or unmixed (one single text only) (Galen, Comm. Hipp. Epidem. III.4-11).

An early example of the title and number of lines at the end of a text has been found in a papyrus roll of Menander's Sicyonius of the third century BC.11

It is worth noting that a scribe's pay was rated according to the quality of writing and the number of lines. A papyrus of the second century AD. gives the rates "for 10,000 lines, 28 drachmae…. For 6,300 lines, 13 drachmae."

In an attempt to standardise costs and wages throughout the Empire, Diocletian rated a scribe's pay as follows : "to a scribe for the best writing, 100 lines, 25 denarii; for second quality writing 100 lines 20 denarii; to a notary for writing a petition or legal document, 100 lines, 10 denarii." 12

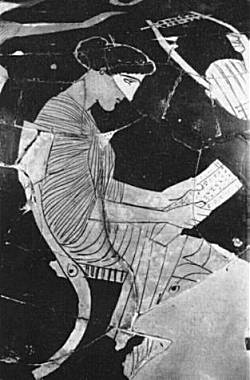

Photo: Sappho reading her book (From an Athenian vase 5th c. BC)