|

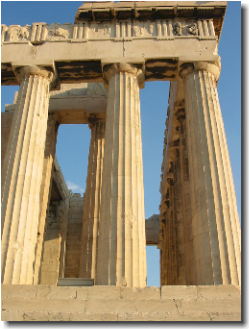

By Evaggelos Vallianatos May 4, 2010 There’s little doubt that the Greeks became the corner stone of the edifice of the West. Their philosophy, science, technology, political theory, democracy, art, dramatic theater, architecture, literature, athletics and mythology gave rise to Western culture, a living and aspiring way of life for much of humanity. I am also a Greek, so the Greek achievement is much more than speculation or pleasant thought for me. I feel it and live it. I am often angry with the Westerners because of their ambivalence and, sometimes, hatred towards their Greek benefactors. I hasten to add that there have always been exceptional Western scholars and philhellenes who devoted their minds and lives to the Greeks. I want to illustrate this mixed feeling with the Parthenon. The occasion for this reflection came from a lecture I attended, 8 March 2010, at the University of Southern California. Dyfri Williams, Research Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum, delivered that lecture, “The Parthenon Sculptures: Ownership, Display and Understanding.” Williams, as if by rote, justified the holding by the British Museum of the plundered Parthenon treasures. I enjoyed seeing pictures of the Parthenon sculptures, but I found the reasons why the British government refuses to return the Parthenon “marbles” to Greece unacceptable — and not a little insulting. But before I focus on the British looting of the Parthenon, and the continuing cultural imperialism of the United Kingdom, some background throws light on more than the British rape of the Parthenon. The Athenians erected the Parthenon in 447-432 BCE on their Akropolis for two reasons: honoring their patron goddess, Athena Parthenos, the virgin daughter of Zeus, and thanking the gods, particularly Athena, for their victory over the Persians. Athena was Athena Polias, the protector of the polis. Athena was the goddess of wisdom, arts, crafts and war. For the first millennium of its life, the Parthenon was the shining light of Hellenic culture: a religious, democratic, architectural, and artistic jewel unsurpassed in beauty and craft. Ploutarchos, a priest of Apollon and a prolific writer who lived about five centuries after the founding of the Parthenon, said the Parthenon, untouched by time, was created for all time.The Parthenon, however, did not exist in isolation. The temple did well only when the Greeks were masters of their country, a political reality that had changed dramatically by the time when Ploutarchos was admiring the grandeur of the temple of Athena. The Romans incorporated Greece into their empire in 146 BCE. The Romans, like later “protectors” of Greece, loved and hated the Greeks. But the Roman crisis in Greece became acute in the fourth century when the Roman Emperor Constantine made the one-god religion of Christianity state religion, overthrowing the millennial polytheism of the Greeks and Romans. Christianity immediately marched into Greece and declared war against the many gods of the Greeks, including Athena honored in the Parthenon. In 484, the Christian Emperor Zeno inflicted the first major blow against the Parthenon. He pillaged the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Athena created by Pheidias. In the sixth century, the Christians were responsible for unfathomable sacrilege with their conversion of the temple of Athena to a church. They also caused irreparable damage not merely to the structure of the building but to its sculpture as well. The Parthenon had 92 high-relief metopes or decorated slabs above the colonnade. The art of the metopes represented in beautiful marble sculpture the mythic origins of the divine and secular world of the Greeks: the battles of the gods and the giants; the victory of the Greeks over the Amazons; the struggle of the centaurs and the Lapiths and the Trojan War. On the triangular pediments one could see the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus and the contest of Athena and Poseidon for Athens. There was also the low-relief, 160-meter long, frieze decorating the inner building of the Parthenon with the exquisite procession of the Athens’ best at the Panathenaia, Athens’ Olympics in honor of the birthday of Athena. All in all, the sculpture of the Parthenon was a pictorial history of Athens, a proud message of Greek origins and a celebration of freedom. The Christians, like other barbarians that attacked the Parthenon sculptures, scratched out Greek history and wrote their own. They hacked Parthenon statues to pieces and defaced, mutilated, and smashed the sculpture of a number of metopes and other sculpture in other places of the temple. They punched windows through the frieze. When the Turks captured Greece in 1453, they also added sacrilege and destruction to the Parthenon, which they made into a mosque. In 1673, the Venetians bombarded the Parthenon, wrecking the building. The next attack against the Parthenon came in early 1800s from the “civilized” Christian Europeans, especially Lord Elgin who served as the British ambassador to the Turks. Elgin and his agents bribed the Turks to give them a free hand with the surviving sculpture of the Parthenon. The Turks cared less about the Parthenon, so the agents of Elgin, furiously and with extreme violence, sawed off just about every sculpture in the metopes and frieze, smashing in the process plenty of sculpture and damaging the building even more. They took intact slabs of metopes and frieze, including a caryatid from the Erechtheion, to England where they are now in the British Museum. Edward Dodwell, a traveler who witnessed how the agents of Elgin removed the sculpture from the Parthenon in 1801 and 1805, spoke about the despoliation of the Parthenon of its finest sculpture, the smashing of a magnificent cornice and a pediment and other statues crushing to the ground; the Parthenon, he said, was reduced to “a state of shattered desolation.” Lord Byron also denounced Elgin’s plunder of the Parthenon, calling Elgin a spoiler who rivaled the Goths and the Turks. The looting and destruction of the Parthenon by Elgin sparked a more widespread stealing of Greek culture. European missionaries and other visitors to Greece, armed with hammers, roamed the country and grabbed whatever piece of art they could find, steal or buy from Greeks and Turks. During the Greek Revolution in the 1820s, general John Makrygiannes stopped a couple of Greek soldiers from selling ancient artifacts to foreigners. He told them “we fought for these antiquities.” Once Greece won her independence from the Turks in 1828, foreign plunder of Greek sculpture around the Akropolis and elsewhere continued but at a slower pace. Finally, by the late nineteenth century, the Greek archaeological service had cleared the Parthenon and the Akropolis from all alien additions from Christians and Moslems. In the twentieth century, the Greek government started asking the British to return the sculpture Elgin had pillaged from the Parthenon. Melina Merkouri, Greek Minister of Culture in the 1980s and early 1990s, was right saying the Parthenon sculpture was “the soul of Greece.” This language offended the British who disputed Greek cultural continuity and resented Greek nationalism. After all, the British remembered the Greeks of the Ionian Islands and Cyprus who revolted against them. In the case of Cyprus, the British encouraged the Turks to nullify Cypriot independence. The Turks obliged and, in 1974, invaded Cyprus with British and American blessings and military support. The British also like to quote a Turkish order giving Elgin “legal” ground for his cultural atrocity, the violent removal and destruction of Parthenon sculpture. They conveniently ignore that the Turks had no legal standing in Greece, at least no more legal standing than the Nazis enjoyed in the 1940s in occupied Europe. Second, British officials pretend that the Parthenon sculpture in their possession receives great care, which Greece, they claim, could never give. During 1937 – 1938, the caretakers at the British Museum inflicted irreparable damage to the Parthenon sculpture. They scrubbed the statues with chemicals and equipment to make them “more white.” And rather than revealing what happened, the British Museum covered up the truth for decades. William St. Clair, British author of “Lord Elgin and the Marbles,” a 1998 book on “the controversial history of the Parthenon sculptures,” concluded that the “stewardship” of the Parthenon sculptures by the British Museum for more than half a century was “a cynical sham,” which forfeited “the British claim to a trusteeship.” He is right. Time has come for the Parthenon sculpture of the British Museum to join its other half in the new Akropolis museum the Greeks built just for that purpose. In the celebrations during the dedication of the Akropolis Museum in 2009, the Greek Minister of Culture Antonis Samaras spoke about the “hostage” of the Parthenon sculpture at the British Museum. Yes, returning the Elgin marbles to Athens would be the right thing to do. It would be the only path to reconciliation between the British and the Greek people. Indeed, the Parthenon means a lot to the Greeks. They love it as a concrete example of the greatness of their ancient culture. Reuniting the sculptures of the Parthenon would also be an act of respect for the integrity of the Greek culture, which, like the other Europeans, the British have used successfully for building their own civilization. At a time of tension and violence, the return of the Elgin marbles to Greece would be an act of Renaissance humanism that may sow seeds of peace and philhellenism in the Mediterranean and the world. Besides, in 2012, the Olympics that are as Greek as the Parthenon will be celebrated in London. What more of an opportune time for the United Kingdom to return the Parthenon treasure to its Greek home and show the world its appreciation for all it has benefited from Hellenic culture. Evaggelos Vallianatos, Ph.D., is the author of several books, including “The Passion of the Greeks.” |